| ὄρνις γάρ σφιν ἐπῆλθε περησέμεναι μεμαῶσιν

αἰετὸς ὑψιπέτης ἐπ᾽ ἀριστερὰ λαὸν ἐέργων

φοινήεντα δράκοντα φέρων ὀνύχεσσι πέλωρον

ζωὸν ἔτ᾽ ἀσπαίροντα, καὶ οὔ πω λήθετο χάρμης,

κόψε γὰρ αὐτὸν ἔχοντα κατὰ στῆθος παρὰ δειρὴν

ἰδνωθεὶς ὀπίσω: ὃ δ᾽ ἀπὸ ἕθεν ἧκε χαμᾶζε

ἀλγήσας ὀδύνῃσι, μέσῳ δ᾽ ἐνὶ κάββαλ᾽ ὁμίλῳ,

αὐτὸς δὲ κλάγξας πέτετο πνοιῇς ἀνέμοιο.

Jove's bird on sounding pinions beat the skies;

A bleeding serpent of enormous size

His talons trussed; alive, and curling round,

He stung the bird, whose throat received the wound:

Mad with the smart, he drops the fatal prey,

In airy circle wings his painful way,

Floats on the winds, and rends the heaven with cries;

Amidst the host the fallen serpent lies.

(Homer, Iliad XII ll. 200–7, tr. Alexander Pope.)

|

As I said previously, I think that the myth of Isis describes the macrocosm, the myth of Osiris describes the mesocosm, and the myth of Horus describes the microcosm. Meditating on the first, therefore, taught me all sorts of interesting things about the structure of the cosmos. Meditating on the second can, presumably, teach us many things about society, but I confess that (as something of a hermit and a misanthrope) my meditations on the topic have not been very fruitful. But the last is, perhaps, the most interesting of the three to me, because, given that Fire has descended and divided, meditating on it should teach us what we can do about it.

Alas, though, what Plutarch gives us to work with is so sparse! So little of the ancient mysteries are recorded, and Plutarch has explicitly neutered much of what little was available in the interests of propriety. I have endeavored to reconstruct as much of the myth as I can from other sources, but even with those, there is not a lot to work with. (We do happen to have a papyrus specifically concerning this part of the myth, but it's very fragmentary and pretty weird, and I had trouble making much use of it.) So, just like in the Isis and Osiris myths, I've wished to attach an equivalent Greek myth to compare against. I had two candidates especially to dig into for this.

The first was the myth of Apollo, which is recounted in the Homeric Hymn to Apollo. (This is pretty reasonable since Apollo is implicitly related to Horus by Homer, Odyssey XV 525–6; and explicitly equated with Horus by Herodotus, History II cxliv; Diodorus Siculus, Library of History I xxv; Plutarch, Isis and Osiris XII; etc.; and Leto is explicitly equated with Isis by Isidorus, the Oxyrhynchus papyrus, etc.) In that myth, Zeus is Osiris; Hera, Set; Leto (Lycian lada, "wife"), Isis; Asteria ("starry," cf. astral), Nephthys; Apollo, Horus; Artemis (here, daughter of Zeus and Asteria rather than Apollo's twin), Anubis; and Delos, Buto. Leto wanders before giving birth to Apollo in Delos in the same way that Isis wanders before giving birth to Horus in Buto; Leto does not nurse Apollo but he is fed ambrosia and nectar in the same way that Isis does not nurse Diktys; finally, Apollo slays the Delphic serpent in the same way that Horus's men slay the serpent chasing Tewaret. The Apollo myth came to Greece by way of Lycia—presumably this is why Apollo was on the side of the Trojans in the Iliad?—and since the myth claims the first priests of Apollo were sailors from Crete, I suppose that the transmission of this myth is from Egypt, to Crete, to Lycia, to Greece.

The second was the myth of Io, which is recounted in Pseudo-Apollodorus, Library II i. (Again, this is pretty reasonable since Io is explicitly equated with Isis by Diodorus Siculus, Library of History, I xxiv; Ovid, Metamorphoses IX l. 666 ff.; the Oxyrhynchus papyrus; the Suda; etc.) Io is turned into a cow in the same way Isis's head is replaced with a cow's; Hermes frees Io in the same way as Thoth rescues Isis; Hera induces Io to wander in the same way as Set induces Isis to wander; Io gives birth to Epaphus when she reaches Egypt in the same way as Isis gives birth to Horus upon her return to Egypt; Hera's kidnapping of Epaphus causes Io to search for him in the same way as Set's dismemberment of Osiris causes Isis to search for him, producing Horus; the queen of Byblos nurses Epaphus in the same way as Isis "nurses" Diktys; and finally, upon her return to Egypt, Io becomes queen and institutes the mysteries in the same way as Isis institutes the mysteries after finding Osiris's pieces. Since Io is said to be the ancestor of a great many heroes (Perseus, Cadmus, Heracles, Minos, etc.)—some of whom are directly related to Dionysus—I suppose that those myths all share some chain of transmission, though it is difficult to say exactly how.

Sadly, since only rags and tatters match up—and not even in order!—neither shed a lot of light on our myth. While pondering this in my perplexity, though, my angel (ever a tease) posed a riddle to me, which lead me to realize that the story of Tiresias advising Odysseus in Hades (Odyssey XI) is the mirror image of Osiris training Horus from Hades. Tiresias prophesies the last leg of Odysseus's homeward journey, and the structure of this prophecy matches closely with the Horus myth:

| #

| Plutarch, Isis and Osiris; Diodorus, Library of History; Manetho, History of Egypt; Papyrus Sallier IV; Pyramid Texts

| Homer, Odyssey

|

| D1

| Osiris visits Horus from Hades, trains him for battle, and tests Horus with questions. Horus answers satisfactorily.

| Odysseus goes to Hades, summons Tiresias, and asks him for advice. Tiresias answers. Odysseus steels himself for the challenges ahead.

|

| D2

| Many of Set's allies switch allegience to Horus, including his concubine Tewaret, who is chased by a serpent which Horus's men cut into pieces.

| Odysseus encounters and escapes from the Sirens, Scylla, and Charybdis.

|

| D3

| Horus defeats Set in battle. During the battle, Horus castrates Set and Set removes Horus's eye.

| Odysseus comes to the island of Thrinacia. Helios loses his cattle. Odysseus loses his men and ship.

|

| D4

| Horus delivers Set as a prisoner to Isis. Isis releases Set. Horus is furious, beheads Isis, and claims kingship of Egypt.

| Odysseus washes ashore on Ogygia and is detained by Calypso, but he spurns her advances.

|

| D5

| Thoth replaces Isis's head with a cow's.

| [cf. D7]

|

| D6

| Set takes Horus to court over the legitimacy of his rule. Thoth argues persuasively in favor of Horus. The gods rule in favor of Horus.

| Athena beseeches Zeus to allow Odysseus to return home. Zeus agrees.

|

| D7

| [cf. D5]

| Hermes tells Calypso that Zeus demands she let Odysseus go. Calypso helps Odysseus build a raft.

|

| D8

| Set returns Horus's eye.

| Odysseus comes, with difficulty, to Scheria; begs aid of king Alcinous; and tells his story. The king gives Odysseus gifts and ferries him to Ithaca.

|

| D9

| Horus defeats Set in battle a second time.

| Odysseus comes to Ithaca, finds his home ransacked by suitors after Penelope, and defeats them with the help of Athena.

|

| D10

| Horus defeats Set in battle a third time, becomes undisputed king of Egypt, and reconciles with Set.

| Tiresias foretells (but it does not occur in the Odyssey) that Odysseus must find a land where the sea is unknown and propitiate Poseidon there, and that if he does so, he will live comfortably to an old age and die peacefully.

|

I find the parallels between these two narratives compelling, and will need to reread the Odyssey with the Isis and Osiris myths in mind. I have, in the past, been fairly critical of using Homer as a theological source, but one cannot dispute that the blind Chian casts a long shadow over the philosophers; his stories obviously came from somewhere, and these days I am becoming increasingly suspicious that "somewhere" means "Egypt" in the same way that "Western philosophy" means "Plato." (Plutarch (Isis and Osiris XXXIV) says as much, and there are those legends that Homer studied under the "imagination of Egypt;" cf. Photius, Library CXC; Eustathius on the Odyssey I.) Anyway, the linking of Horus and Odysseus puts us on firm ground, since Plotinus (Enneads I vi §8–9) and Thomas Taylor (The Wanderings of Ulysses) both explain what Odysseus's journey means in a manner agreeable, it seems to me, with the interpretation of Empedocles that I have been working with, so let's take a look.

Osiris's questions to Horus (D1, above) run like this:

Osiris. What do you think is the best thing?

Horus. To avenge one's parents!

Osiris. Okay. What animal is most useful to a soldier?

Horus thinks for a moment. A horse.

Osiris raises his eyebrows. Why?

Horus. Well, a lion would be better in a pinch, but without a horse, how could you annihilate the fleeing enemy!?

Osiris beams. Yes! You are ready, my son!

I should emphasize how out-of-character this is for Osiris: he is elsewhere described as gentle, charming, laughter-loving, fond of dance, and he went out of his way (as king of Egypt) to civilize the world through pursuation rather than force. Horus, on the other hand, is bloodthirsty and merciless. If you've ever seen a falcon eat, perhaps that's unsurprising, but in terms of the myth, I believe Horus is so determined because there is no half-assing spirituality: if one is to try to ascend, they must devote their whole being to it; if they do not, they cannot become whole, and the soul must be whole to be like Fire, which is indivisible. So even though Osiris is, himself, peaceful and gentle, he encourages Horus's resolve of Necessity: after all, Horus is the son of stern-and-severe Isis, too, and having the backbone she furnishes is table stakes for the difficult climb up the mountain. Tiresias says as much to Odysseus, too: "You seek to return home, mighty Odysseus, and home is sweet as honey; but heaven will make your voyage hard and dangerous, because I do not think the Earthshaker will fail to see you and he is furious at you for blinding his son." Odysseus is less bloodthirsty than Horus, but nonetheless resigns himself to his fate: "Alas, Tiresias, if that is the thread which the gods have spun, then I have no say in the matter."

Then we have the three battles between Horus and Set, only the first of which is really described in any detail. In this part of the myth, I don't think Set is acting as Air itself, but rather as something of a proxy for Strife; this is because Air is separatory from the perspective of Fire, and Horus is "avenging" Osiris. The three battles represent the individual soul transcending each of Earth, Water, and Air, respectively, in the process of returning to its Source. This isn't as straightforward as it seems at first, though, because of a couple structural considerations stemming from how the natures of the four roots. First, Earth and Water are both material and separate out under the influence of Strife simultaneously, so a soul still requires the use of a material body until it has transcended both. Second, Fire is indivisible and descends whole and therefore must reascend whole; this implies that the third battle with Set cannot occur until all souls are ready to transcend Air simultaneously, which is something that only occurs at the end of time, when the cosmos again comes completely under the influence of Love.

What does it mean for the soul to transcend the roots? Plato's Diotima discusses it (in a roundabout sort of way) in the Symposium (201D ff.) and Plotinus discusses it in Enneads I ii "On Virtue" (which Porphyry summarizes, more lucidly I think, in the 34th of his Sentences). One's Earthy part is the physical body, the soul's "bestial" part: to transcend Earth is to move beyond purely sensory experience and gain the ability to consider ideals on the same level as them; this is the mastery of Plato's "civic virtues," the ability to live a civilized life as a man rather than the savage life of an animal. One's Watery part is one's desiring faculty, its hungers and needs: to transcend Water is to move beyond material desires; this is the mastery of Plotinus's "purificatory virtues," the ability to cease to concern oneself with material things in favor of spiritual things. One's Airy part is the soul's emotional faculty, its ability to experience and judge things from an individual perspective: to transcend Air is to move beyond individuality completely; this is the mastery of Plotinus's "contemplative virtues," the ability to process things from all perspectives simultaneously, rather than one-at-a-time. Diotima says concordantly that one climbs the ladder of love from personal beauty to general beauty, from general beauty to abstract beauty, and from abstract beauty to universal beauty. Meanwhile, Porphyry explains that mastery of the civic virtues makes one a human; the purificatory virtues, an angel; and the contemplative virtues, a god (indeed, in this context, the god Osiris-Horus specifically, as all souls return to their Source).

Only the first of these is illustrated in the Horus myth, the transcending of Earth. That it is Earth and not Water is made clear in a few ways. First, we have the killing of the snake: we have seen destroyed phalluses already, with Isis cutting Osiris out of the heather stalk (representing matter being made to support other-than-bestial forms) and with the fish eating Osiris's penis (representing society being structured to foster an other-than-bestial life). The killing of the snake itself seems to be one "hacking to pieces" (analysing and overcoming) their bestial nature. Second, Tewaret is a concubine of Set's—a "lesser Nephthys," perhaps a being of Water rather than Water itself—which suggests to me the harnessing of desire (for peace, for comfort, for security, etc.) to create a civilized existence; that is, it is for this desire that the bestial nature is hacked to pieces. Third, Horus's violent deposing of Isis is a pretty literal—if violent, calling to mind the words of another initiate—description of the individual soul transcending Earth.

In the Odysseus story, this first battle plays out between Ææa (representing the bestial life, which is why everyone is a pig except Odysseus, who has Hermes—intelligence—guiding him) and Ogygia (home to Calypso, the seductive daughter of Atlas "who separates Earth from Heaven"). Odysseus encounters many monsters and troubles, and while he manages to escape from each (with difficulty), his men are unable to control themselves and are not so lucky, and so Odysseus comes to Ogygia alone. From this, Thomas Taylor (riffing on Plotinus, Enneads II iii §13?) makes the excellent point that there are three categories of souls. The first, which he likens to Heracles (and I might liken to Pythagoras or the Buddha or Jesus), is mighty and is capable of saving both themselves and others; if Odysseus was one of these, he and his men would have traveled swiftly back to Ithaca. No, Odysseus (who I might liken to dear Porphyry), rather, is of the second category, strong enough to save himself but not strong enough to save others, and this is why he struggles and strains to return to Ithaca, and manages it only after tremendous delay with neither his men nor his ship nor his plunder. (The third category is the mass of men, strong enough to accomplish nothing but get eaten by some monster or drown at sea—that is, to be lost in sense experience. Here, I disagree a little with Taylor, as eventually all souls must return to their Source, but it may take such time and suffering as to make Odysseus's journey seem luxurious by comparison.)

The episode with Horus's eye is pretty opaque, and in fact Plutarch omits it entirely from his recording of the myth, but it becomes much more understandable when we compare it to the Odysseus story. Notice how, in D3, Horus loses his eye while Odysseus loses his ship, while in D8, Horus gets his eye back and Odysseus is ferried to Ithaca on a Phæacian ship; these imply that Horus's eye and Odysseus's ship are, symbolically, the same. I didn't notice any references describing it specifically, but Odysseus's original ship is presumably a normal one (if of fine quality); on the other hand, Homer tells us the Phæacian ships are magical, the gift of Poseidon and "swift as a thought." Recall what Empedocles says of sight:

γαίῃ μὲν γὰρ γαῖαν ὀπώπαμεν, ὕδατι δ' ὕδωρ,

αἰθέρι δ' αἰθέρα δῖον, ἀτὰρ πυρὶ πῦρ ἀίδηλον,

στοργὴν δὲ στοργῇ, νεῖκος δέ τε νείκει λυγρῷ.

We see Earth by Earth, Water by Water,

Aither by divine Aither, Fire by destructive Fire,

Love by Love, and Strife by baneful Strife.

I think Horus's eye and Odysseus's ship represent what one is capable of seeing: Horus's original (mundane) eye is the Earth-eye by which we see Earth, while the returned eye is the (magical) Water-eye by which we see Water. (In theory, there is also a (divine) Air-eye by which we see Air, but this last is inherent to the individual soul and it doesn't need a vehicle to house it, which is why Horus doesn't lose his eye a second time and why Odysseus's final journey must be made on foot and without the use of a ship at all.) It is of interest to me that Horus does without his eye for a while, able neither to properly see Earth nor Water, since I have experienced this myself: I have nearly lost the ability to perceive and enjoy the beauty of Earth, but I am only very slowly developing the ability to see and appreciate higher beauty, so there is something of a gap where I seem to have a foot in both worlds but it feels more like having a foot in neither. (I wonder if this is what St. John of the Cross was talking about when he describes "the dark night of the soul.") In any case, just as we see Odysseus climbing the ladder of roots in his use of vehicles, we see the same thing reiterated in the guidance he receives: in escaping from Circe and Calypso (transcending Earth), Odysseus is guided by Hermes, who (in terms I've discussed previously) is his intelligence; in reclaiming his household (transcending Water), Odysseus is guided by Athena, who is his wisdom; however, Odysseus receives no help at all in propitiating Poseidon (transcending Air), since in doing so he is guided only by Truth.

At the same time as the soul loses its eye for material things, Set is said to lose his testicles, for which the Pythagoreans' famous censure of "beans" comes to mind:

An old and false opinion has seized men and prevailed, that the philosopher Pythagoras [...] abstained from the bean, which the Greeks call κύαμος. In accordance with this opinion, the poet Callimachus wrote:

As Pythagoras, I tell you too:

Abstain from beans, a malign food.

[...] It seems that the cause of the error about not dining on beans is that in the poem of Empedocles, who followed Pythagoras's teachings, this verse is found:

δειλοί, πάνδειλοι, κυάμων ἄπο χεῖρας ἔχεσθαι

Wretches, utter wretches, keep your hands off beans!

For most people thought that κύαμοι refered to the legume, as is the common usage. But those who have studied Empedocles's poem with more care and learning say that in this place κύαμοι means "testicles" and that these are called κύαμοι in the Pythagorean manner, cryptically and symbolically, because they conceive [punning κύαμος "bean" with κυεῖν "to conceive"] and supply the power of human reproduction. So, in that verse Empedocles wanted to draw men away not from eating beans but from a desire for sex.

(Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights IV xi.)

The first battle closes with Set in chains, brought by a triumphant Horus before Queen Isis. In the same way that gentle Osiris acts bizarrely in this myth, so too does his wife: normally severe and uncompromising, here she meekly lets her husband's murderer go free. The reason for this is, of course, that Earth is the extremity of the cosmos and most under the influence of Strife: Isis has no power over Set, whether she wishes it or not. Horus's decapitating of Isis and claiming the throne demonstrates that he asserts control over Earth, and is no longer bound to submit to her will: having mastered the civic virtues, he now is bound by a higher law than those of the Law-Giver. The replacement of Isis's head with that of a cow's shows that, rather than Earth being the master (as a human), she is now a docile beast of burden (as a cow): since Horus has mastered being human, the body can now be recognized as a mere tool rather than one's whole being. This is similar to Odysseus on Ogygia: Calypso is ever trying to seduce Odysseus, but even with all her blandishments, Odysseus simply no longer cares for creature-comforts, even those of a goddess, but is completely detached from them and ever sits on the shore looking towards Ithaca and hoping to see even a wisp of smoke on the horizon. Calypso even promises him immortality, but Calypso's sort of immortality is just more turnings on the wheel of rebirth.

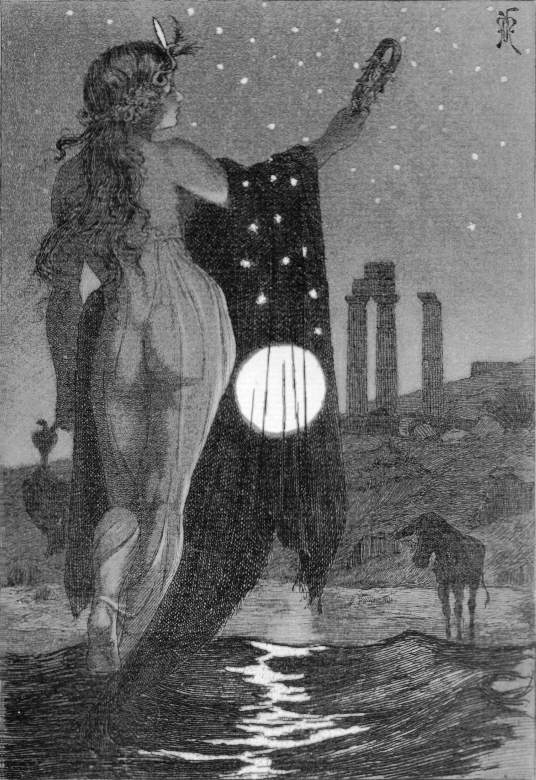

While I am following what I think is a Pythagorean take on the myth, it must be noted that Manetho (Epitome of Physical Doctrines) and Diodorus Siculus (Library of History I xi) say that the Egyptians came up with all this by watching the Sun and Moon in their revolutions in the sky. I have avoided following that interpretation for now, though it has much to recommend it. (For example, the fourteen pieces that Osiris is chopped into is the two week period of the waxing Moon; Set is said to have killed Osiris under the light of the full Moon; Set is likened to the eclipses, which "eat" the Sun; etc.) But consider: if the Sun is Osiris, the soul, and the Moon is Isis, the body, then the Moon is full when she is furthest from the Sun; this is when the soul is lost in matter and the body shines brightest. But just after this, as the Moon begins to return to the Sun, she wanes, and at the very point when the body is less bright than the soul (that is, less than half of it is illuminated), the Moon becomes crescent-shaped. Perhaps this is also what is signified by Isis taking on the horns of a cow.

After the triumph over Earth comes the trial of Horus, and given the placement in the myth and the overall symbolism of a courtroom, this must surely refer to the judgement of the dead for their deeds and misdeeds in life (cf. J. Gwyn Griffiths, The Conflict of Horus and Seth III). Unlike the cautionary episodes in the myth of Isis (e. g. of Diktys and his brother), this episode is salutary: Horus has acted righteously and is rewarded for his behavior, as his eye is returned to him and his authority is legitimized. In the Odyssey, Zeus judges Odysseus to be "beyond all men in understanding and in sacrifice to the deathless gods" and lends the explicit support of Olympus to his return home. The message here is that if one acts righteously and devotes themselves to heaven, then heaven will return the favor and support them in their upward journey. Since, as I have said, one must transcend both Earth and Water to become free of material existence, and since Water has not yet been transcended by this point in the narrative, then I must suppose that this refers to reincarnation into circumstances more conducive to their spiritual growth.

Reincarnation wasn't a widespread belief in ancient Greece (cf. Homer, Iliad XXI l. 569); in fact, it was considered a peculiarity, and perhaps the keynote, of Pythagoras's teachings:

[Pythagoras] was accustomed to speak of himself in this manner: that he had formerly been Æthalides, and had been accounted the son of Mercury, and that Mercury had desired him to select any gift he pleased except immortality; he accordingly had requested that, whether living or dead, he might preserve the memory of what had happened to him. [...] At a subsequent period he passed into Euphorbus, and was wounded by Menelaus, and while he was Euphorbus, he used to say that he had formerly been Æthalides, and that he had received as a gift from Mercury the perpetual transmigration of his soul, so that it was constantly transmigrating and passing into whatever plants or animals it pleased, and he had also received the gift of knowing and recollecting all that his soul had suffered in hell, and what sufferings too are endured by the rest of the souls.

But after Euphorbus died, he said that his soul had passed into Hermotimus, and when he wished to convince people of this, he went into the territory of the Branchidæ, and going into the temple of Apollo, he showed his shield which Menelaus had dedicated there as an offering, for he said that he, when he sailed from Troy, had offered up his shield which was already getting worn out, to Apollo, and that nothing remained but the ivory face which was on it. When Hermotimus died, then he said that he had become Pyrrhus, a fisherman of Delos, and that he still recollected everything, how he had been formerly Æthalides, then Euphorbus, then Hermotimus, and then Pyrrhus. When Pyrrhus died, he became Pythagoras, and he still recollected all the aforementioned circumstances.

(Diogenes Laertius, The Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers VIII i §4. Aulus Gellius (Attic Nights IV xi) adds that Pythagoras also claimed to have been "a beautiful courtesan named Alco.")

Empedocles famously echoes Pythagoras's teachings:

ἤδη γάρ ποτ' ἐγὼ γενόμην κοῦρός τε κόρη τε

θάμνος τ' οἰωνός τε καὶ ἐξ άλὸς ἔμπορος ἰχθύς.

For I have already become a boy and a girl

And a bush and a bird and a fish from the sea.

This is one of those teachings that causes modern commentators to suppose that Pythagoras got his doctrines from the East, but I see no reason not to suppose that the Egyptians had some similar belief. Herodotus says so explicitly (Histories II cxxiii); meanwhile, Diogenes Laertius (Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers VIII ii §2) tells us that Plato was an initiate of the Pythagoreans but, like Empedocles, was expelled for revealing the mysteries in writing; and he espouses the doctrine in the Republic, and in the Phædrus (246A–9D) he goes further and says that normal souls must struggle for ten thousand years to "grow their wings," but those souls who choose philosophical lives three times in a row "will have wings given them." In the Odyssey, after Zeus judges Odysseus favorably, he has three days' swim ahead of him before he is given the use of the Phæacian ship, "swift as wings," exhibiting nearly identical symbolism. Since the return voyage part of the Odyssey fits the Horus myth so closely, it seems plausible to me that the teaching ultimately comes from Heliopolis but the detail was either not available to Plutarch, or else was excised from the myth along with Isis's beheading and the loss of Horus's eye. (It's hard to say which! In describing the Eleusinian mysteries (On the Man in the Moon XXVII ff.), Plutarch speaks of triumphant souls being given "wreaths of feathers," and while he connects the Isis myth to his explanation there (Isis and Osiris XLIV ff.) it's perhaps more likely that he's simply following Plato.)

Not only does wisdom support Odysseus in those philosophical lives, but Zeus gives explicit divine aid comes in the form of the White Goddess (Ino, daughter of Cadmus, whom Zeus divinized), who gives Odysseus her veil so that he might safely reach land, which seems to me to symbolise those dæmons who call to the souls nearing the upper world as (for example) those of Socrates or Plotinus.

In any case, after the three philosophical lives, Horus defeats Set a second time, meanwhile Odysseus is "given wings" in the form of the Phæacian ship, returns to Ithaca, and sets his house in order, turning out all things discordant and foreign. (Indeed, the suitors remind me of nothing so much as of Plotinus's analogy of the assembly (Enneads IV iv §17), where the "brawlers and roarers" overpower the wise-but-quiet words of the best; but here, the best overrules them.) The individual soul has thus traversed the ocean (transcended Water) and become a hero: no longer do they require a material body, but they proceed to live in the world of Air as a pure soul alongside the golden race. What does the soul do there? I really don't know, and I suspect we couldn't comprehend it anyway: Horus is the child of Fire and Earth, and so those two realms must be completely natural to him; similarly, he was nursed by Water, and so while he is a foreigner there, it is at least familiar to him; but he lacks that same sort of connection with Air, and so it must be rather alien. I suppose, like Socrates (Phædo 67A–C) that we should simply have the good hope that when we reach there, that we shall "be with the pure and know all that is pure."

There remains only the third battle between Horus and Set, and for Odysseus to propitiate Poseidon. I think it very appropriate that, while it is foretold by Tiresias, the Odyssey ends before Odysseus actually goes and accomplishes it. This is because Fire is indivisible: in the same way as it must descend whole, it must also reascend whole. This means that the soul finally rejoining its Source and Goal can only occur for all souls simultaneously countless eons from now, after the last souls finally leave the material world behind and the roots begin to collapse together again. At that point, this cycle of the cosmos will end, all will be joined in Love (as Tiresias says, "your people shall be happy round you"), and a new cycle will begin where Fire will descend into matter anew (as Tiresias says, "death shall come to you from the sea"). All this is beyond the scope of the individual, and that is why the Odyssey, which is about the individual soul, ends before it takes place; in any case, I imagine this final battle to be much more sedate, requiring none of the tremendous trauma of the first two: merely long ages of time.

And with that, we're through the mysteries of Isis, Osiris, and Horus! (Phew!) I never expected to spend five months on a mere nine pages of prose, and yet exploring them has helped me to make a lot more sense of Greek mythology, the philosophical tradition, and my own personal theology and place in the cosmos; so I can see why my angel led me to it and encouraged me to study it.

While I'm satisfied with my first—erm, first-and-a-half?—pass through the myth itself, there are still a few bits and pieces I'd like to follow-up on. What's the deal with Perseus and Andromeda? There's supposedly an echo of the myth in the Iliad XIV, is that so? I've shown the second half of the Odyssey to fit the myth, but what about the rest of it? I've mentioned that I think Apuleius was an initiate of Isis, Osiris, and Horus; but does his myth of Cupid and Psyche fit, too? Is there anything to be gained by more deeply considering the Sun and Moon cycle as the origin of the myth? These are all interesting to me and you may see a smattering of smaller and less formal posts on them in the coming weeks and months as I have a chance to explore them, but they're tangential to the myth itself and so I'm considering them more in the mode of appendices.

One of those bits and pieces, though, is Achilles; I've been re-reading the Iliad over the holidays, so why don't I deal with him briefly, here? I mentioned before that his birth and childhood match the myth of Isis; it is also the case, I think, that his prophecy and death match the myth of Horus. Achilles's signature characteristic is wrath, just like Horus's is vengeance. At Horus's trial, it is said that Geb, his grandfather, was the judge; in the same way, Achilles's grandfather, Æacus, is the judge of the dead in the underworld. Just like Horus, Achilles is a demi-god, possessing a mortal half (his body) and an immortal half (his name); and just like Odysseus with Penelope and Calypso, Achilles got to choose which half was which: he could live forever as a nobody, or die young but be immortalized in glory. Achilles made the right choice, favoring soul over body. Will you?