Earlier this year, I spent a month or so going over the Corpus Hermeticum. I didn't think a whole lot of it at the time; I had just figured it was something worth studying to round out my exploration of Hellenistic philosophy a little. But my angel pulled my attention back to it a couple weeks ago: some of the images it contains helped to crystalize my thoughts concerning the myth. I suppose this should not be so surprising, since Hermetism developed out of a blending of Egyptian (including Heliopolitan), Greek (including Pythagorean), and Assyrian religious sensibilities... consider, for example, the following in light of my last post:

I saw an endless vision in which everything became light—clear and joyful—and in seeing the vision I came to love it. After a little while, darkness arose separately and descended—fearful and gloomy—coiling sinuously so that it looked to me like a snake. Then the darkness changed into something of a watery nature, indescribably agitated and smoking like a fire; it produced an unspeakable wailing roar. Then an inarticulate cry like the voice of fire came forth from it. But from the light a holy word mounted upon the watery nature, and untempered fire leapt up from the watery nature to the height above. The fire was nimble and piercing and active as well, and because the air was light it followed after spirit and rose up to the fire away from earth and water so that it seemed suspended from the fire. Earth and water stayed behind, mixed with one another, so that earth could not be distinguished from water, but they were stirred to hear by the spiritual word that moved upon them.

(Corpus Hermeticum I "Poimandres" iv–v, as translated by Brian P. Copenhaver.)

The plunging of fire above into water below, being infused with a holy word, and rising again above earth and water sounds quite a bit like Empedocles's separation and recombination of roots, does it not? Indeed, in his summary of Empedocles, Hippolytus gives us (Refutation of All Heresies VII xvii) the elegant image of the Demiurge acting as a blacksmith, taking souls as if they are irons and successively plunging them into fire and water in order to temper them. With all that successive expansion and contraction, is it any wonder that mortal life is so stressful?

We have talked about how Osiris is Fire; Set, Air; Isis, Earth; and Nephthys, Water; but we have not talked about what the roots really are. I think there's good reason for that: nobody knows. This is not to be critical of any commentator in particular, but rather simply because we are speaking about the gods, and the gods are beyond human comprehension: you can't categorize the gods because they're the categories! So the best we can do is to classify phenomena in terms of the gods, as Fiery or Airy or Earthy or Watery; this will help us to sketch broadly some of the meanings of the myth, but of course the myth has as many different meanings as the gods themselves do.

One of Empedocles's fragments gives a poetic illustration of the properties of some of the roots which can help us:

ἠέλιον μὲν λαμπρὸν ὁρᾶν καὶ θερμὸν ἁπάντῃ, [...]

ὄμβρον δ' ἐν πᾶσι δνοφόεντά τε ῥιγαλέον τε·

ἐκ δ' αἴης προρέουσι θελυμνά τε καὶ στερεωπά.

the Sun, bright to look on and hot in every respect, [...]

and rain, in all things dark and cold;

and there flow from the Earth things dense and solid.

Our old friend Proclus further provides a rigorous classification scheme (Commentary on the Timaeus III xxxviii–xliv), describing the roots in terms of three properties: ὀξύτης "sharpness" (vs. ἀμβλύτης "bluntness") indicating that Fire pervades the other roots and suffuses the cosmos; λεπτομέρεια "fineness" (vs. παχυμέρεια "coarseness"), indicating that Fire and Air are spiritual while Water and Earth are material; and εὐκινησία "ease of motion" (vs. ἀκινησία "stasis"), indicating that Earth is bound by inertia while the other roots are not. Each root varies from the next densest root by the presence or absence of exactly one property, as follows:

| Fire

| sharp

| subtle

| mobile

|

| Air

| blunt

| subtle

| mobile

|

| Water

| blunt

| dense

| mobile

|

| Earth

| blunt

| dense

| static

|

This classification scheme is Proclus's, but there's support for it elsewhere in the tradition: Plato (Timaeus 56A ff., 58B ff.) and Aristotle (On Generation and Corruption II iii) make the distinction between sharp Fire and the other roots; Hippolytus (Refutation of All Heresies VII xvii) summarizes Empedocles by calling Water and Earth material, but Fire and Air immaterial; etc.

There are other traditional schemes of classifying the elements—Aristotle, for example, famously classifies them as secondary to the properties hot, cold, wet, and dry—but Proclus demonstrates that these disagree with Empedocles and so I will ignore them.

In light of these properties and the metaphysics they imply, let me hazard a rough guess at one possible way of interpreting what the gods refer to in the myth, with the understanding that there are surely many others that are all valid.

Osiris, as Fire, is (among other things) energy and light. I have in the past equated light with the soul, and I think that applies here, with a caveat. Osiris is what the Greeks call νοῦς "Mind," but this isn't what we normally think of today as the mind, the thing that thinks; it is more like pure, unreflective consciousness (hence why Osiris is naive and innocent). Susan Brind Morrow (The Dawning Moon of the Mind I) says that his name (𓊨𓁹, Ꜣusjrj) means "the seat of the eye," presumably whatever that thing is that "sits behind the eyes." (This strikes me as a very curious conception, since I don't think one's consciousness sits anywhere, but it seems that I am unusual in this regard.) When Plato and Proclus say that Fire is "sharp," they are saying that it is able to penetrate through the other roots, suffusing the entire cosmos with Light and Life (an image also evoked by Air and Water being transparent). Pythagoras tells us that the Monad is Fiery; Plotinus tells us that the Mind is unitary; and the Poimanders corroborates:

[Poimandres said,] "I am the light you saw: mind, your god [...]. The light-giving word who comes from mind is the son of god. [...] This is what you must know: that in you which sees and hears is the word of the lord, but your mind is god the father; they are not divided from one another for their union is life."

Thus I suppose there is only one Fire—that is to say, there is only one consciousness, and our experience of individuality is merely that consciousness "seeing" through individual bodies, the same as a single Fire emits many rays of light. Presumably consciousness is universal and indivisible because meaning is separate from judgement: Osiris does not discriminate good from bad, but considers everything as good and right just as it is (which is why everything is joyful and perfect at the beginning of the myth when he rules in Egypt). But, just like Osiris's "essence" is born as Horus, so too does the universal Mind contain "the light-giving word," the individual soul, within it. This is reiterated by Aetius, who tells us (Doxographi Graeci CCCXCII) that Empedocles says "that soul and mind are the same thing:" Fire is what animates the cosmos, and there is no corner so dark that it does not penetrate to.

Set, as Air, is (among other things) the world of Hesiod's golden race (and the righteous part of the lower races) and which Plotinus cryptically describes as vast and diverse. It is perhaps unsurprising that our notions of this world are vague, as Air is, of course, invisible and sparse. Air mediates between energetic Fire and dense matter: it is therefore, somewhat paradoxically, separatory from the perspective of Fire (hence why it is Set that tricks Osiris into a box and chops him into pieces) but unitive from the perspective of matter (hence why Set is also the protector of Ra in his underworld journey).

Isis, as Earth, is (among other things) the familiar Material Cosmos which gives form and structure to things, and of which your body makes up a very tiny part. It is her skirt that the Western scientific tradition has spent the last four hundred years trying (and failing) to peek under. (This failure is because Earth, being a god, is ever-fecund: the more Fire works upon her, the more she brings forth. This is why Plotinus calls Nature infinitely-divisible and why scientists find more and more subatomic particles the closer and closer they look.) I had noted previously that her name in Egyptian (𓊨𓏏, Ꜣusat) simply means "the seat;" I think this is because Earth, as the densest root, is the foundation of the world upon which all else rests. Isis is depicted as stern and severe because Earth is static: Nature's laws cannot be broken—woe unto them who attempt it—and it is for this reason that she and Demeter are both called θεσμοφόρος (thesmophoros, "law-giving").

Nephthys, as Water, is also matter but of a much more subtle sort: she is (among other things) the Underworld, the world of Hesiod's silver race (and the unrighteous part of the lower races), the substance of dreams, mental imagery, ghosts, etc., and of which your "lower soul" ("astral body") makes up a very tiny part. Empedocles's commentators all call Water "nutritive" because it connects dense Earth to the all-pervading light (energy, vitality, etc.) of the immaterial, and it is for this reason that while Isis is the mother of Horus, Nephthys is said to be his nurse; this association is echoed by Homer (Odyssey XI) when Odysseus first offers a libation of milk to the dead.

Those are the gods in macrocosm. In the microcosm, we have the Fiery, Airy, Watery, and Earthy parts of one's self, and I personally have been wondering if this is where Plato got his tripartite theory of soul: one's Fiery part is the λόγος (logos, usually translated "reason," but also "word," as in the Poimandres, above), the seat of consciousness; one's Airy part is the θυμός (thumos, "passion"), the seat of emotion; and one's Watery part is the ἐπιθυμία (epithumia, "desire"), the seat of appetite, since Empedocles says that desire is caused by a lack of nutrition. (One's Earthy part is of course the body, the seat of sensation, and hence is not counted as a "part of soul" at all.) I think we should be careful of words like "reason" for Fire: we think of "reason" as one's capacity for discursive or logical thought, but Empedocles is emphatic that thinking occurs in the blood because it is as close to a perfect mix of the roots in the body as possible: thought involves all of one's capacities. Instead, I think "word" is meant in the sense of "the expression of an idea:" the soul is the expression of a unique idea in the divine Mind, which is just what Horus is with respect to Osiris.

It is interesting to compare (my interpretation of) Empedocles's roots with Plotinus, since while there are broad similarities, we have a few differences, too. Empedocles's roots are co-eval, while Plotinus's hypostases are explicitly ordered. Empedocles's roots all co-exist and indeed seem to mix to various degrees, while Plotinus's hypostases seem much more discrete and separate from each other. Plotinus separates Mind and souls and makes them eternal, while Empedocles equates them and makes them merely immortal. Plotinus considers the Mind to be the demiurge ("Creator"), while Empedocles assigns this role to Strife (as the force that brings beings into becoming) rather than Fire. I haven't spent a lot of time unpacking these differences, but I think doing so would be worthwhile; my "Bayesian prior," so to speak, is to assume that Plotinus is a refinement of Empedocles, since while we don't know what became of Empedocles—certainly, he didn't jump into Etna!—we have on unimpeachable authority what became of Plotinus! Alas, it's impossible to know what the Egyptian priests throughout the millennia believed and taught (and, indeed, what may have become of them).

With those keys in hand, let's proceed to the mysteries of Isis. Hesiod gave us the authoritative Greek version of the theogony, but the authoritative version of the Demeter myth comes from the Homeric Hymns, and this is what I have compared Plutarch with. The two agree so closely that the relationship between them is certain:

| #

| Plutarch, Isis and Osiris; Diodorus, Library of History; Manetho, History of Egypt

| Homeric Hymn to Demeter

|

| B1

| [cf. B3]

| Hades asks Zeus for permission to marry Persephone. Zeus consents.

|

| B2

| Isis discovers the arts of civilization. Osiris teaches them to the Egyptians.

| Persephone and the Oceanides pick flowers at Nysa.

|

| B3

| Set is jealous of Osiris.

| [cf. B1]

|

| B4

| Set makes a beautifully-ornamented box sized to fix Osiris exactly.

| Zeus asks Gaia for assistance. Gaia causes a magical narcissus to grow.

|

| B5

| Set and seventy-two conspirators trick Osiris into the box, seal it with molten lead, and push it into the Nile.

| Persephone picks the narcissus, causing a hole to open in the ground. Hades kidnaps Persephone through the hole.

|

| B6

| Set becomes king of Egypt. Isis becomes a fugitive.

| [cf. B13]

|

| B7

| Pan and the satyrs learn of Osiris's death and tell Isis. Isis cuts off a lock of her hair and puts on garments of mourning.

| Demeter hears Persephone scream as she is kidnapped.

|

| B8

| Isis grieves and wanders in search of Osiris.

| Demeter grieves and wanders in search of Persephone for nine days.

|

| B9

| Some children tell Isis that they saw the box float into the sea.

| Hekate tells Isis that Persephone was kidnapped, but that she does not know by whom.

|

| B10

| Isis meets Nephthys and learns that she (by Osiris) gave birth to Anubis, but exposed him out of fear of Set. Isis searches for Anubis. Dogs lead Isis to Anubis. Isis raises Anubis to be her guardian and attendant.

| Hekate travels with Demeter.

|

| B11

| The box lands in a patch of heather near Byblos in Phoenecia. The heather grows to exceptional size, enclosing the box within its stalk. King Malkander is so impressed by the stalk of heather that he cuts it down for a pillar in his house.

|

|

| B12

| Isis learns of the heather at Byblos by divine inspiration.

| Helios tells Demeter that Hades kidnapped Persephone with Zeus's blessing.

|

| B13

| [cf. B6]

| Demeter, furious at Zeus, quits Olympus and wanders in the guise of a mortal.

|

| B14

| Isis travels to Byblos, sits beside a spring, weeps, and speaks to nobody.

| Demeter travels to Eleusis and sits beside a spring.

|

| B15

| Queen Astarte's maids come by the spring. Isis plaits their hair and perfumes them with ambrosia. Astarte sees her maids beautifully made up and sends for Isis.

| The daughters of lord Keleos meet Demeter. Demeter asks for work. The daughters speak to lady Metaneira on her behalf. Metaneira sends for Demeter.

|

| B16

| Isis ingratiates herself with Astarte.

| Metaneira has an epiphany of Demeter and offers her her seat. Demeter refuses. Iambe sets Demeter a humble seat. Demeter accepts and grieves. Iambe makes Demeter laugh. Metaneira offers Demeter wine. Demeter refuses. Metaneira offers Demeter a kykeon. Demeter accepts.

|

| B17

| Astarte appoints Isis nurse of Diktys.

| Metaneira appoints Demeter nurse of Demophoon.

|

| B18

| Isis nurses Diktys with her finger rather than her breast, while at night she gradually burns away his mortal part while herself transforming into a swallow, flying around the pillar, and bewailing Osiris.

| Demeter breathes on Demophoon and anoints him with ambrosia rather than nursing him, and gradually burns away the child's mortal part in secret.

|

| B19

| Astarte eventually sees Diktys burning and cries out, which deprives the child of immortality.

| Metaneira eventually sees Demophoon burning and cries out, which deprives the child of immortality.

|

| B20

| Isis explains herself and asks for the pillar. Astarte consents. Isis cuts the box out of the pillar, wraps the remains of the pillar in linen, perfumes it, and entrusts it to the royal family as a relic.

| Demeter scolds Metaneira, charges Keleos to build a temple for her, and teaches the mysteries to the people that they may propitiate her for Metaneira's error.

|

| B21

| Isis laments her husband so profoundly that the queen's [unnamed] younger son dies.

| Demeter laments her daughter so profoundly that famine overtakes the earth.

|

| B22

| Isis takes the box and Diktys and sails from Byblos. The Phaedrus river delays the journey. Isis dries it up in spite.

| Zeus summons Demeter to Olympus. Demeter refuses until she sees Persephone.

|

| B23

| Isis opens the box, sees Osiris's body, and grieves.

| Zeus asks Hades to bring Persephone to visit Demeter. Hades agrees, secretly forces Persephone to eat a pomegranate seed, and brings Persephone to Demeter. Persephone tells Demeter her story.

|

| B24

| Diktys is curious and peeks into the box. Isis is furious and gives him such an awful look that he dies of fright.

|

|

| B25

|

| Hekate becomes Persephone's attendant and companion.

|

| B26

| Isis returns to Buto with the box.

| Zeus summons Demeter to Olympus again. She agrees and goes.

|

| B27

| Set finds the box, opens it, divides Osiris into pieces, and scatters them across Egypt.

| Zeus decrees that Persephone will spend a third of the year with Hades and two thirds of the year with Demeter.

|

This part of the myth has two broad sections: B1–14 and 26–7 (which describes Isis wandering), and B14–25 (which describes Isis instituting her mysteries). The Osiris part of the myth also has a section on the institution of his mysteries, and while it is very brief, we could probably reconstruct a bit from the comparable Assyrian, Phrygian, and Greek mysteries (no doubt there were lots of penises involved). The Horus part of the myth lacks such a section: I suppose that it must have existed but any details are lost to us.

While the Isis myth and the Demeter myth both share nearly identical structures, I think that they have very different meanings. The latter is, of course, about the descent of an individual soul into matter due to desire and getting stuck in the cycle of reincarnation. But Osiris isn't an individual soul: Horus is, and he will not be seen until the end of the Isis myth's sequel. This myth, then, is universal in scope: it is about the descent and loss of consciousness in matter in its entirety, and the slow, slow process by which material bodies are evolved to be capable of admitting the reascent of souls at all. That is, we are speaking of the creation of humanity.

Initially, Osiris rules Egypt, teaching the Egyptians all good things. Egypt is the spiritual world of Fire and Air: Osiris is Fire itself and the Egyptians are Empedocles's daimons, the denizens of Air which Osiris "illuminates"—that is, gives life and consciousness to. Hesiod seems to imply, and Plotinus says explicitly, that some great souls never descend into the material world of Water and Earth at all; I think the myth teaches the same thing, since Osiris teaches them to refrain from cannbalism, which is what Empedocles says causes daimons to fall. In the same way, in the Demeter myth, Nysa is the spiritual world and the Oceanids are those souls that do not fall. Egypt and Nysa are both the sky, and the Egyptians and Oceanids (the daughters of the heavenly Ocean) are, of course, the stars. (Indeed, because of the ease of identifying Egypt and the Egyptians, or Nysa and the Oceanids, with the stars, I wonder if my previous association of Nut with Love was incorrect: perhaps Nut is simply the spiritual world of Fire and Air, while Geb is the material world of Water and Earth. Something to consider further—alas, so many of my speculations raise more questions than answers!)

Plotinus tells us that the reason for the descent of souls is that the Mind endeavors to be comprehensive, conscious of all that it can possibly be conscious of. This is why Osiris desires the box and allows himself to be tricked into it: the descent of souls isn't an individual sin so much as a universally necessary byproduct of the Mind's comprehensivity: it is not man that falls, but Man—or, perhaps, the entire category of beings of which humanity constitutes but a small part. The Nile is the Milky Way, the "bridge" by which the divine (the greater world, the galaxy) connects to the material (the smaller world, the solar system). Byblos is the Earth. So Osiris being sealed in Set's box, dumped in the Nile, coming to rest in Byblos, and being encased in a stalk of heather shows Mind being encased first in Air, then in Water, and finally in Earth: matter is not initially capable of supporting consciousness, and so Mind in the lower world is lost, incapable of expression, "dead."

And that is just why Isis wanders and frets so over Osiris: there need to be forms such that the Mind can express itself in Earth as completely as possible, but Earth is so solid and fixed that it is difficult to contort it into a shape that makes this possible, and so it takes long, long ages of time to accomplish. That is, Isis's wandering represents the process of evolution. We think of this as a modern notion invented by Charles Darwin, but several of Empedocles's fragments discuss it, saying that the first creatures appeared out of the earth parthenogenically, and gradually combined and mixed into ever-more sophisticated forms which can exemplify, however imperfectly, the attributes of the higher world:

οὐλοφυεῖς μὲν πρῶτα τύποι χθονὸς ἐξανέτελλον,

ἀμφοτέρων ὕδατός τε καὶ εἴδεος αἶσαν ἔχοντες·

τοὺς μὲν πῦρ ἀνέπεμπε θέλον πρὸς ὁμοῖον ἱκέσθαι,

οὔτε τί πω μελέων ἐρατὸν δέμας ἐμφαίνοντας,

οὔτ' ἐνοπὴν οὔτ' αὖ ἐπιχώριον ἀνδράσι γυῖον. [...]

ᾗ πολλαὶ μὲν κόρσαι ἀναύχενες ἐβλάστησαν.

γυμνοὶ δ' ἐπλάζοντο βραχίονες εὔνιδες ὤμων,

ὄμματά τ' οἶ' ἐμπλανᾶτο πενητεύοντα μετώπων[, ...]

αὐτὰρ ἐπεὶ κατὰ μεῖζον ἐμίσγετο δαίμονι δαίμων,

ταῦτά τε συμπίπτεσκον, ὅπῃ συνέκυρσεν ἕκαστα,

ἄλλα τε πρὸς τοῖς πολλὰ διηνεκῆ ἐξεγένοντο. [...]

πολλὰ μὲν ἀμφιπρόσωπα καὶ ἀμφίστερνα φύεσθαι,

βουγενῆ ἀνδρόπρῳρα, τὰ δ' ἔμπαλιν ἐξανατέλλειν

ἀνδροφυῆ βούκρανα, μεμιγμένα τῇ μὲν ἀπ' ἀνδρῶν

τῇ δὲ γυναικοφυῆ, στείροις ἠσκημένα γυίοις.

First there came up from the Earth whole-natured outlines

having a share of both Water and Heat;

Fire sent them up, wanting to reach its like,

and they did not yet show any lovely frame of limbs,

nor voice nor again the male "limb." [...]

Then sprouted up many heads without necks

and arms wandered naked, bereft of shoulders,

and eyes roamed alone bereft of brows[, ...]

But when daimon mixed more with daimon,

and these things came together as each happened to meet

and many others in addition to these were constantly emerging. [...]

Many grew with two heads or two torsos;

oxen with the heads of men, and others arose as

bull-headed men, and still others with mixed male

and female natures and so rendered sterile.

Note the presence of chance in Empedocles's description and reproductive fitness in this process: many bizarre and useless combinations are produced, but as Aristotle (Physics II viii) comments, "wherever all the parts came about as if they had been appropriately designed to, such creatures survived; but those which grew otherwise died out, just like Empedocles says his 'oxen with the heads of men' did."

In the Demeter myth, Persephone—the individual soul—already exists and is fully-formed in the mind of god before she falls; but in the Egyptian myth, it is universal Osiris who falls, containing Horus the Elder—the potential for individual souls—within him. Note also how Empedocles speaks of "daimon mixing more with daimon:" the Neoplatonist conception of souls as individual, discrete atoms clearly can't apply if they are capable of mixing! Instead, I wonder if the teaching here is that soul descends en masse like a cloud of fog, and it is only when it has reached the ground does the water vapor begin to condense into droplets, some greater, some less, which can finally reascend as unified wholes. Thus when Isis wanders aimlessly and when Empedocles speaks of chance, this seems to be saying that the descending soul is amorphous and that the individual soul that will eventually arise doesn't necessarily have a fixed form or unique place in the cosmos from the outset: it is only when Isis brings Osiris back to the Egyptian coast, which represents the creation of material forms (like humanity) that are on the very edge of the upper world and capable of individuation and reascent, that the amorphous group soul can begin to differentiate and individual souls begins to form. Until that point, we're dealing with something more akin to an undifferentiated continuum of soul-stuff; while Osiris is always one, it is Isis, in a sense, which draws the lines between which parts of Osiris go into one kind of creature and which go into another, and thus what eventually constitutes the "individual soul." It is uncomfortable for me to give chance much of a place in a universe ruled by Providence, but Plotinus says that happenstance is involved in the sublunary world, and perhaps this is the reason why Isis is said to invent while Osiris is said to teach: what Isis brings forth by chance, Osiris imbues with purpose? Certainly, it at least makes good sense of Iamblichus's and Proclus's argument that a human soul can't reincarnate as a beast: once the human part of the soul-continuum has differentiated, it is no longer the right "shape" to fit in bodies adapted to other parts of the soul-continuum. In any case, once Horus—whose purpose is to take flight—is born, it is hard to see how lower bodies can further that purpose, so even if it is possible, it must be impractical.

As a consequence of the above difference between the two myths, I think Demeter's wandering must mean something different from Isis's. Hesiod tells us (Theogony, l. 713) that "a brazen anvil falling down from Heaven nine nights and days would reach the Earth upon the tenth;" that is, nine days is presumably how long it takes for her to get from Heaven to Earth. As soon as she reaches the Earth, she meets with Hekate and Helios, the Moon and Sun, also suggesting this. But if this is so, her quitting Olympus in a huff afterwards seems to be confused: did she not already quit it?

Speaking of Hekate, we have not yet discussed Anubis, her counterpart in the Isis myth. By being the child of bright Fire and dark Water, he is obviously native to both the upper and lower worlds simultaneously, which of course is why he is said to be a psychopomp. But I think there's another side to it: Fire is the first of the roots while Water is the last, hence Anubis is the child of cause and effect; that is to say, he is the link between them, or karma. (He sits in judgement in Duat because one reviews their conscious actions (Fire) when they are dead (Water), as any number of near-death experiencers can tell you.) The dogs that lead Isis to Anubis are, as Pythagoras tells us, the planets, which are the mechanism by which karma operates: the circumstances or energies that cause us to have experiences (and to develop experience) in the lower world. Hippolytus (Refutation of all Heresies I iv) says that Empedocles believed that evils only existed in the sublunary world, and this is why Anubis attends to Isis—what we call "evil" is simply the consequences of selfish action. The equivalent of Anubis in the Demeter myth is Hekate, who follows Demeter (representing natural law generally) and eventually clings to Persephone (representing individual karma); the general Greek equivalent is Artemis (sibling of Apollo in the same way Anubis is the sibling of Horus): consider the myth of Actaeon, who is devoured by his own dogs (that is, his own deeds). Artemis and Hekate are both associated with the moon because this is where their influence begins.

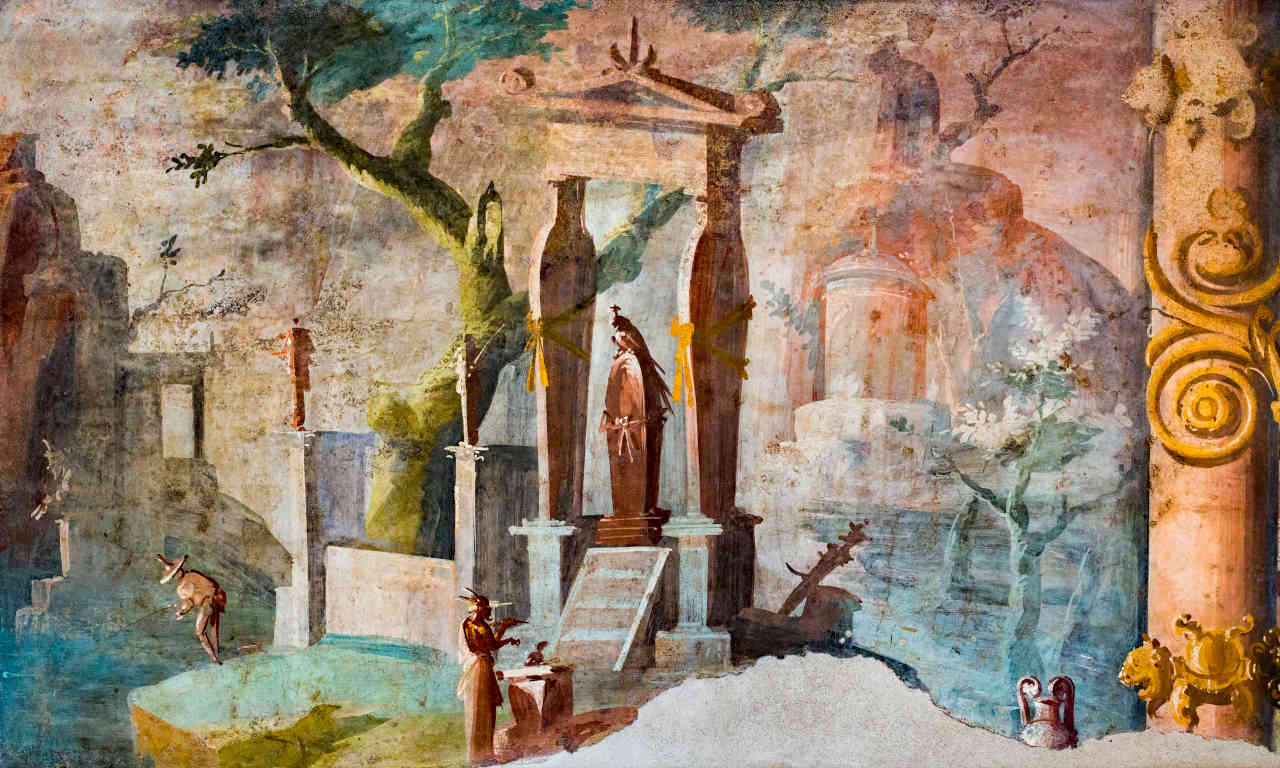

The remainder of the myth concerns the institution of the mysteries themselves, and I think that this part switches gears significantly, since it appears to no longer be speaking of cosmic processes, but rather of the "ground rules" of the mysteries that initiates must abide by. No longer is Isis, Earth; or Osiris, Fire; etc.: Isis is now the initiator, Osiris is the mystery teachings themselves, Astarte and Malkander are the initiate, Diktys and the unnamed younger son are the initiate's personal Horus (soul) and Anubis (karma), etc.

Malkander is most likely a Greek transliteration of Phoenecian Melqart ("King of the City"); Astarte and Melqart were the local Isis and Osiris of Tyre. Indeed, Ishtar/Astarte/Aphrodite and Dumuzid/Hadad/Baal ("King")/Adonis ("Lord") were the local Isis and Osiris of many different cities in the Near East, just as Demeter and Zeus were at Eleusis. I think all this syncretism is because the mysteries were intended to be as tolerant and anti-dogmatic as possible; indeed, we see many, many local reflections of the myth: most of the heroes (ahem, Horuses) of Greek myth have echoes of the Isis myth in them, suggesting that they weren't historical kings but rather the names attached to local mystery cults. My favorite example of this is Achilles: Pseudo-Apollodorus (Library III xiii §6) tells us how Thetis would feed him ambrosia by day and burn him in a fire at night to make him immortal, but Peleus's outcry halted this. (He even says that the etymology of Achilles is ἀ-χεῖλος "without lips," indicating that Thetis never nursed him with her breast, just like Isis.)

What are these "ground rules?" Isis speaking to nobody and making-over Astarte's maids teaches how the mysteries did not proselytize, but how people were supposed to come to them of their own volition, whether by seeing the effects they had on other initiates (as here in the myth), or by being so directed in a dream (cf. Pausanias, Descriptions of Greece X xxxii; Apuleius, Golden Ass XI), or by intense personal drive (Apuleius, Apology §§53–6). Malkander making Osiris into a pillar in his house indicates that the initiate should take the mystery teachings into their heart (and, indeed, make them of central importance). Isis suckling Diktys with her finger rather than her breast indicates feeding one's soul spiritual food rather than indulging in material pleasures. Isis burning Diktys in the fire indicates meekly bearing material misfortunes. Astarte's outcry depriving Diktys of immortality is a censure of discussing the mysteries: one is only to contemplate them within their heart. Isis lamenting Osiris and killing Astarte's younger son thereby indicates that one must not bewail their lot: one can only become immortal by embracing their karma as a friend and guide, rather than a curse. Diktys peeking in the box to see Osiris and dying is a censure of trying to pry into the mysteries without having been legitimately initiated.

Isis's homeward journey with Osiris seems to me to be something of a reference to overcoming the elements: the heather stalk is earth, the Phaedrus river is water, the wind coming off the river is air, and Osiris himself is fire. But I don't think these are the actual Earth, Water, Air, and Fire, but rather merely the vulgar forms those principles take when reflected in Earth: the passage through them represents the mystery teachings giving one authority to overcome, or even command, the material world, just as Empedocles says:

φάρμακα δ' ὅσσα γεγᾶσι κακῶν καὶ γήραος ἄλκαρ

πεύσῃ, ἐπεὶ μούνῳ σοι ἐγὼ κρανέω τάδε πάντα.

παύσεις δ' ἀκαμάτων ἀνέμων μένος οἵ τ' ἐπὶ γαῖαν [· ...]

καὶ πάλιν, ἤν κ' ἐθέλῃσθα, παλίντιτα πνεύματ' ἐπάξεις· [...]

ἄξεις δ' ἐξ Ἀίδαο καταφθιμένου μένος ἀνδρός. [...]

εἰ γὰρ καὶ ἐν σφ' ἁδινῇσιν ὑπὸ πραπίδεσσιν ἐρείσας

εὐμενέως καθαρῇσιν ἐποπτεύσεις μελέτῃσιν,

ταῦτά τέ σοι μάλα πάντα δι' αἰῶνος παρέσονται,

ἄλλα τε πόλλ' ἀπὸ τω-νδε κτήσεαι· αὐτὰ γὰρ αὔξει

ταῦτ' εἰς ἦθος ἕκαστον, ὅπῃ φύσις ἐστὶν ἑκάστῳ.

All the potions which there are as a defence against evils and old age

you shall learn, since for you alone will I accomplish all these things.

You shall put a stop to the strength of tireless winds, [...]

and again, if you wish, you shall bring the winds back again, [...]

and you shall bring from Hades the strength of a man who has died. [...]

For if, thrusting [my words] deep down into your crowded heart,

you gaze on them in kindly fashion, with pure meditations,

absolutely all these things will be with you throughout your life,

and from these you acquire many others, for these things themselves

will expand to form each character, according to the nature of each.

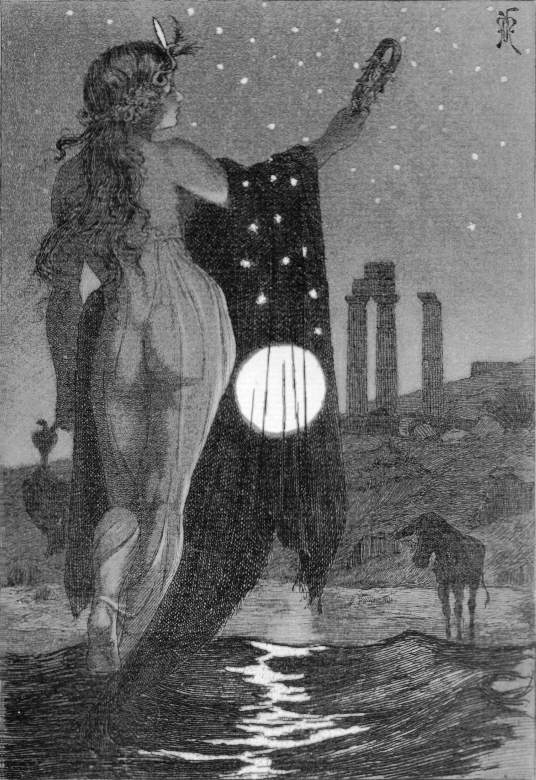

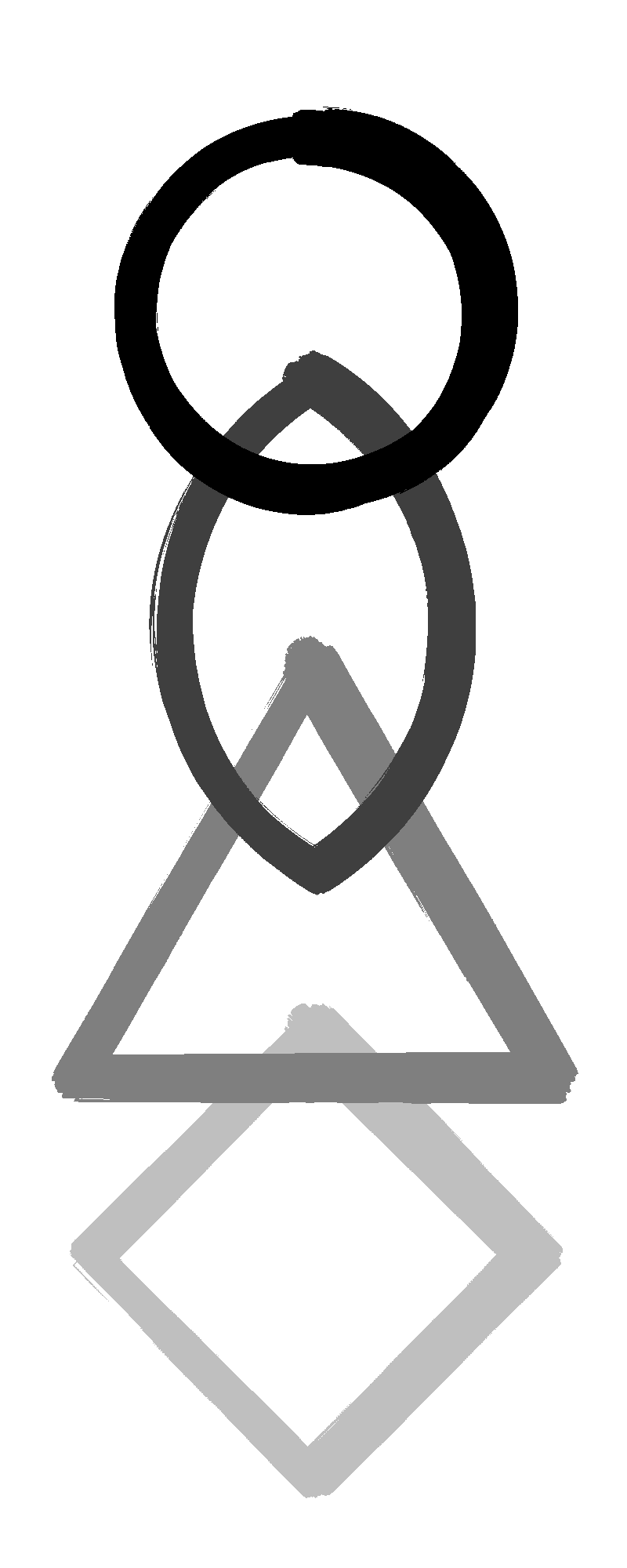

Finally, there's one last thing I'd like to mention. When she becomes aware of Osiris's death, Isis puts on a mourning garment. As far as I can tell, this was a black linen cloth which was tied with a rope or long shawl, which went around the neck and arms as was tied between the breasts, supporting them, keeping the garment secure, and shaping it to the body. This girdle, I think, is the tyet knot of Isis, representing the shaping or binding principle, which is the property of Earth. The heather stalk that Osiris was contained within and which grew to prodigious size thereby is, of course, the djed pillar, representative of Mind as a quickening (erm, penetrating) principle, which is the property of Fire. When you combine the form of the tyet with the rigidity of the djed, you get an ankh, which is the symbol of Horus as the union of Earth and Fire, the individual soul, and that greater Life which it might aspire to. I think these three—a small knotted cord, a stalk of heather, and an ankh of reed or something—were made, perfumed, wrapped in linen, and given to initiates as mementos, in order to encourage them to contemplate the mysteries in private long after their initiations.

𓎬 𓊽 𓋹