So I'm presently reading Herodotos through for fun, having only read bits and pieces from him before. Today I came across this:

Ἀπάγονται δὲ οἱ αἰέλουροι ἀποθανόντες ἐς ἱρὰς στέγας, ἔνθα θάπτονται ταριχευθέντες, ἐν Βουβάστι πόλι [...]. τὰς δὲ μυγαλᾶς καὶ τοὺς ἴρηκας ἀπάγουσι ἐς Βουτοῦν πόλιν, τὰς δὲ ἴβις ἐς Ἑρμέω πόλιν.

Dead cats are taken away into sacred buildings, where they are embalmed and buried, in the city of Bubastis [...]. Field mice and falcons are taken away to Buto, ibises to the city of Hermes.

(Herodotos, Histories II §67, as translated by A. D. Godley with minor edits by yours truly.)

This struck me, since Bubastis (hence the cat) was the holy place of Bastet (Artemis/Hekate), while Buto (hence the mouse and falcon) was the holy place of Horos (Apollon), being his birthplace. Now, we're very familiar with cats, but the Greeks weren't; they kept weasels to hunt mice, and while we tell silly stories about cats and mice, they told the same sorts of stories about weasels and mice. Here's a dopey example I ran across back when I was studying Teiresias:

[...] δειπνῆσαι ἐν τοῖς Θέτιδος καὶ Πηλέως γάμοις. ἔνθα ἐρίσαι περὶ κάλλους τήν τε Ἀφροδίτην καὶ τὰς Χάριτας, αἷς ὀνόματα Πασιθέη Καλὴ καὶ Εὐφροσύνη. τὸν δὲ δικάσαντα κρῖναι καλὴν τὴν Καλὴν, ἣν καὶ γῆμαι τὸν Ἥφαιστον, ὅθεν τὴν μὲν Ἀφροδίτην χολωθεῖσαν μεταβαλεῖν αὐτὸν εἰν γυναῖκα χερνῆτιν γραῖαν, τὴν δὲ Καλὴν χάριτας αὐτῇ ἀγαθὰς νεῖμαι καὶ εἰς Κρήτην ἀπαγαγεῖν, ἔνθα ἐρασθῆναι αὐτῆς Ἄραχνον, καὶ μιγέντα αὐχεῖν τῇ Ἀφροδίτῃ μιγῆναι. ἐφ' ᾧ τὴν δαίμονα ὀργισθεῖσαν τὸν μὲν Ἄραχνον μεταβαλεῖν εἰς γαλῆν, Τειρεσίαν δὲ εἰς μῦν, ὅθεν καὶ ὀλίγα φησὶν ἐσθίει ὡς ἐκ γραός, καὶ μαντικός ἐστι διὰ τῶν Τειρεσίαν. ὅτι δὲ μαντικόν τι καὶ ὁ μῦς δηλοῦσιν ὅ τε χειμών, οὗ σημεῖον ἐν καιρῷ οἱ τῶν μυῶν τρισμοὶ, καὶ αἱ ἐκ τῶν οἰκιῶν φυγαὶ, ἃς διαδιδράσκουσιν ὅτε κινδυνεύοιεν καταπεσεῖν.

[Teiresias] dined at the wedding of Thetis and Peleus. A beauty contest between Aphrodite and the Graces, named Pasithea ["the goddess of all," wife of Sleep, hence refreshment], Kale ["beauty"], and Euphrosune ["happiness"], was held there. He was made judge and judged Kale the most beautiful, and she married Hephaistos, which so galled Aphrodite that she turned Teiresias into an old spinster, but Kale made her very beautiful and brought her to Crete, where Arakhnos ["spider"] fell in love with her and, having had sex with her, bragged that he lain with Aphrodite herself. This so infuriated the goddess that she turned Arakhnos into a weasel and Teiresias into a mouse, which is why they say a mouse eats so little (because it is an old woman) and why they say it can tell the future (because it is Teiresias). That it can tell the future is clear because its squeakings are a timely sign of a storm, and that it flees a house in danger of collapse.

(Eustathios of Thessolonike on the Odyssey 1665.48 ff., following Sostratos, Teiresias, as very hastily translated by yours truly—please consider it a mere paraphrase.)

Both of these—the association of Horos with mice and the association of the hero Teiresias with a mouse—of course calls to mind how Khruses, the high priest of Apollon, calls to Apollon Smintheus ("Apollon of the Mouse") to visit a plague upon the Akhaians at the beginning of the Iliad:

κλῦθί μευ ἀργυρότοξ’, ὃς Χρύσην ἀμφιβέβηκας

Κίλλάν τε ζαθέην Τενέδοιό τε ἶφι ἀνάσσεις,

Σμινθεῦ εἴ ποτέ τοι χαρίεντ’ ἐπὶ νηὸν ἔρεψα,

ἢ εἰ δή ποτέ τοι κατὰ πίονα μηρί’ ἔκηα

ταύρων ἠδ’ αἰγῶν, τὸ δέ μοι κρήηνον ἐέλδωρ:

τίσειαν Δαναοὶ ἐμὰ δάκρυα σοῖσι βέλεσσιν.

O Smintheus! sprung from fair Latona's line,

Thou guardian Power of Cilla the divine,

Thou source of light! whom Tenedos adores,

And whose bright presence gilds thy Chrysa's shores;

If e'er with wreaths I hung thy sacred fane,

Or fed the flames with fat of oxen slain;

God of the silver bow! thy shafts employ,

Avenge thy servant, and the Greeks destroy.

(Homer, Iliad I 37–42, as translated by Alexander Pope.)

Evidently the ancients thought this very strange and spent a lot of ink trying to make sense of it. One example, concerning not only Apollon and mice but also weasels, runs like this:

Αἰγύπτιοι μὲν οὖν σέβοντές τε καὶ ἐκθεοῦντες γένη ζῴων διάφορα γέλωτα ὀφλισκάνουσι παρά γε τοῖς πολλοῖς: Θηβαῖοι δὲ σέβουσιν Ἕλληνες ὄντες ὡς ἀκούω γαλῆν, καὶ λέγουσί γε Ἡρακλέους αὐτὴν γενέσθαι τροφόν, ἢ τροφὸν μὲν οὐδαμῶς, καθημένης δὲ ἐπ᾽ ὠδῖσι τῆς Ἀλκμήνης καὶ τεκεῖν οὐ δυναμένης, τὴν δὲ παραδραμεῖν καὶ τοὺς τῶν ὠδίνων λῦσαι δεσμούς, καὶ προελθεῖν τὸν Ἡρακλέα καὶ ἕρπειν ἤδη.

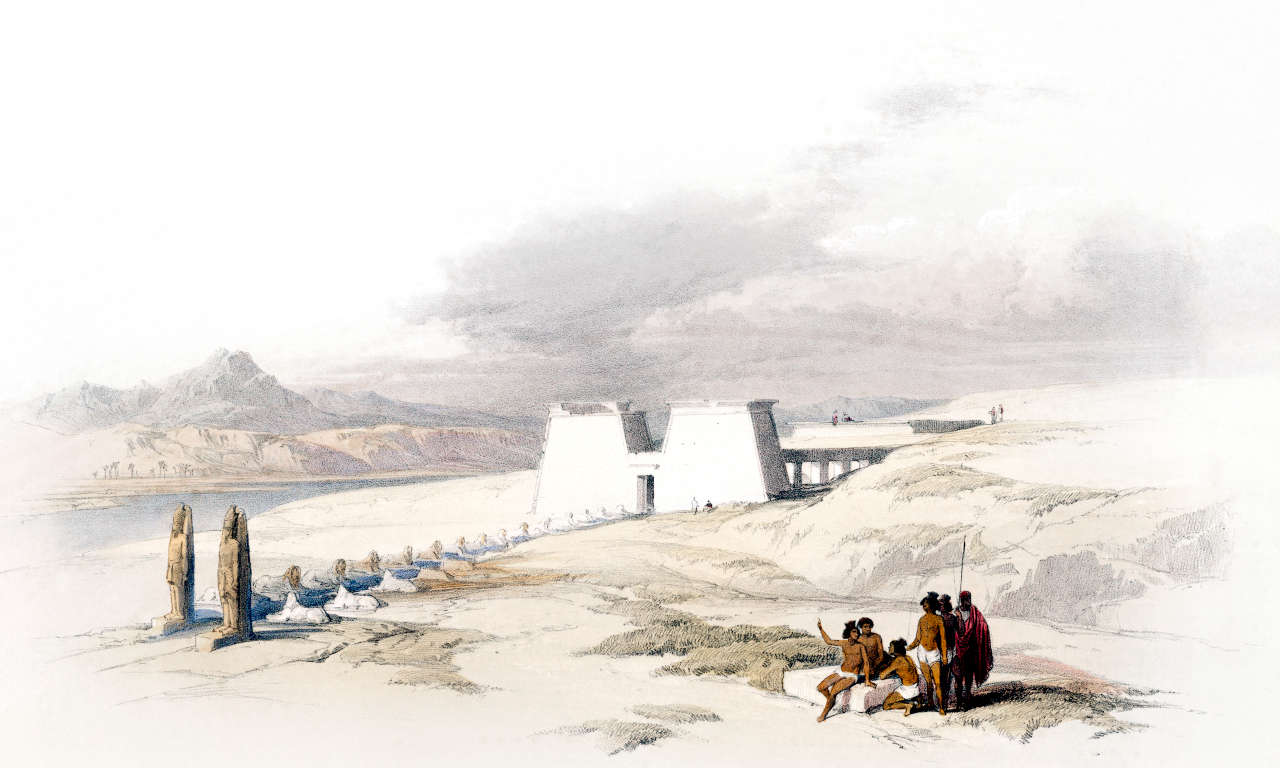

καὶ οἱ τὴν Ἁμαξιτὸν τῆς Τρωάδος κατοικοῦντες μῦν σέβουσιν: ἔνθεν τοι καὶ τὸν Ἀπόλλω τὸν παρ᾽ αὐτοῖς τιμώμενον Σμίνθιον καλοῦσί φασιν. ἔτι γὰρ καὶ τοὺς Αἰολέας καὶ τοὺς Τρῶας τὸν μῦν προσαγορεύειν σμίνθον, ὥσπερ οὖν καὶ Αἰσχύλος ἐν τῷ Σισύφῳ ἀλλ᾽ ἀρουραῖός τίς ἐστι σμίνθος ὧδ᾽ ὑπερφυής. καὶ τρέφονται μὲν ἐν τῷ Σμινθείῳ μύες τιθασοὶ δημοσίας τροφὰς λαμβάνοντες, ὑπὸ δὲ τῷ βωμῷ φωλεύουσι λευκοί, καὶ παρὰ τῷ τρίποδι τοῦ Ἀπόλλωνος ἕστηκε μῦς.

μυθολόγημα δὲ ὑπὲρ τῆσδε τῆς θρησκείας καὶ ἐκεῖνο προσακήκοα. τῶν Αἰολέων καὶ τῶν Τρώων τὰ λήια πολλὰς μυῶν μυριάδας ἐπελθούσας ἄωρα ὑποκείρειν καὶ ἀτελῆ τὰ θέρη τοῖς σπείρασιν ἀποφαίνειν. οὐκοῦν τὸν ἐν Δελφοῖς θεὸν πυνθανομένων εἰπεῖν ὅτι δεῖ θύειν Ἀπόλλωνι Σμινθεῖ, τοὺς δὲ πεισθέντας ἀπαλλαγῆναι τῆς ἐκ τῶν μυῶν ἐπιβουλῆς καὶ τὸν πυρὸν αὐτοῖς ἐς τὸν νενομισμένον ἄμητον ἀφικνεῖσθαι.

ἐπιλέγουσι δὲ ἄρα τούτοις καὶ ἐκεῖνα. ἐς ἀποικίαν Κρητῶν οἱ σταλέντες οἴκοθεν ἔκ τινος τύχης καταλαβούσης αὐτοὺς ἐδεήθησαν τοῦ Πυθίου φῆναί τινα αὐτοῖς χῶρον ἀγαθὸν καὶ ἐς τὸν συνοικισμὸν λυσιτελῆ. ἐκπίπτει δὴ λόγιον, ἔνθα ἂν αὐτοῖς οἱ γηγενεῖς πολεμήσωσιν, ἐνταῦθα καταμεῖναι καὶ ἀναστῆσαι πόλιν. οὐκοῦν ἥκουσι μὲν ἐς τὴν Ἁμαξιτὸν τήνδε καὶ στρατοπεδεύουσιν ὥστε ἀναπαύσασθαι, μυῶν δὲ ἄφατόν τι πλῆθος ἐφερπύσαν τά τε ὄχανα αὐτοῖς τῶν ἀσπίδων διέτραγε καὶ τὰς τῶν τόξων νευρὰς διέφαγεν: οἳ δὲ ἄρα συνέβαλον τούτους ἐκείνους εἶναι τοὺς γηγενεῖς, καὶ μέντοι καὶ ἐς ἀπορίαν ἥκοντες τῶν ἀμυντηρίων τόνδε τὸν χῶρον οἰκίζουσι, καὶ Ἀπόλλωνος ἱδρύονται νεὼν Σμινθίου.

ἡ μὲν οὖν τῶν μυῶν μνήμη προήγαγεν ἡμᾶς ἐς θεολογίαν τινά, χείρους δὲ αὑτῶν οὐ γεγόναμεν καὶ τοιαῦτα προσακούσαντες.

People make fun of the Egyptians for regarding different kinds of animals as gods and worshipping them, but I hear that the Thebaians, despite being Hellenes, worship a weasel, since they say that it was the nurse of Herakles himself when he was born, or if it wasn't his nurse, that when Alkmene was in labor and wasn't able to give birth, it ran by and the bind on her labor was released, and Herakles was born and began to crawl right away.

And those who live in Hamaxitos in the Troad worship a mouse, and they say that for that reason they call Apollon, who they worship, by the name "Smintheus," because even today the Aioleans and the Troadians call the mouse sminthos, just like Aiskulos in his Sisyphus:

But what's so special about a field mouse?

And in the Smintheon they keep tame mice by a tax on the people's food, and white ones live in a hole under the altar, and a mouse stands beside the tripod of Apollon.

And those same people tell me a further story, that many myriads of mice came upon the yet unripe field crops of the Aioleans and the Troadians and cut them from beneath, causing the summer harvest to fail early. Accordingly they asked the god at Delphi and he answered that they must sacrifice to Apollon Smintheus, and they obeyed and were delivered from the treachery of the mice and their wheat attained a normal harvest.

And they also tell me another story on that topic, that a group of Cretans who had met with some bad luck were dispatched to found a colony and asked the Puthia to show them some good place where it would be advantageous to resettle, and the oracle answered that they should stop and raise a city where the "earth-born" attack them. So they came to where Hamaxitos now is and camped to rest for the night, but an uncountable multitude of mice snuck up and, scattering everywhere, ate their shield straps and bowstrings. They made the connection between these mice and the "earth-born," and anyway, now being without a means of protecting themselves [on the road], built a city and a temple to Apollon Smintheus.

Well, the mention of mice led us into some theology, but perhaps we are none the worse for hearing such stories.

(Aelian on the Nature of Animals XII v; following Strabo, Geography XIII i §48; in turn following Kallinos; as very hastily translated by yours truly—please consider it a mere paraphrase.)

But Aelien apparently misses the crucial point that Herakles's weasel was a human originally, and was transformed into a weasel by Hera as punishment for supporting Alkmene. Here is Antoninus Liberalis's account of the story:

Προίτου θυγάτηρ ἐν Θήβαις ἐγένετο Γαλινθιάς. αὕτη παρθένος ἦν συμπαίκτρια καὶ ἑταιρὶς Ἀλκμήνης τῆς Ἠλεκτρύωνος. ἐπεὶ δὲ Ἀλκμήνην ὁ τόκος ἤπειγε τοῦ Ἡρακλέους, Μοῖραι καὶ Εἰλείθυια πρὸς χάριν τῆς Ἥρας κατεῖχον ἐν ταῖς ὠδῖσι τὴν Ἀλκμήνην. καὶ αὗται μὲν ἐκαθέζοντο κρατοῦσαι τὰς ἑαυτῶν χεῖρας· Γαλινθιὰς δὲ δείσασα, μὴ Ἀλκμήνην ἐχστήσωσι βαρυνομένην οἱ πόνοι, δραμοῦσα παρά τε τὰς Μοίρας καὶ τὴν Εἰλείθυιαν ἐξήγγειλεν, ὅτι Διὸς βουλῆ γέγονε τῇ Ἀλκμήνῃ παῖς χόρος· αἱ δὲ ἐκείνων τιμαὶ καταλέλυνται. Πρὸς δὴ τοῦτ' ἔκπληξις ἔλαβε τὰς μοίρας καὶ ἀνῆκαν εὐθὺς τὰς χεῖρας. Ἀλκμήνην δὲ κατέλιπον εὐθὺς αἱ ὠδῖνες· καὶ ἐγένετο Ἡρακλῆς. αἱ δὴ Μοῖραι πένθος ἐποιήσαντο καὶ τῆς Φαλινθιάδος ἀφείλοντο τὴν κορείαν, ὅτι θνητὴ τοὺς θεοὺς ἐξηπάτησε, καὶ αὐτὴν ἐπόησαν δολερὰν γαλῆν καὶ δίαιταν ἔδωκαν ἐν τῷ μυχῷ καὶ ἄμορφον ἀπέδειξαν τὴν εὐνήν· θορίσκεται μὲν γὰρ διὰ τῶν ὠτῶν, τίκτει δ' ἀναφέρουσα τὸ κυούμενον ἐκ το τραχήλου. ταύτην Ἑκάτη πρὸς τῆν μεταβολὴν τῆς ὄψεως ᾤχτειρε καὶ ἀπέδειξεν ἱερὰν αὐτῆς διάκονον· Ἡρακλῆς δ' ἐπεὶ ἠυξήθη, τἠν χάριν ἐμνημόνευσε καὶ αὐτῆς ἐπόησεν ἀφίδρυμα παρὰ τὸν οἶκον καὶ ἱερὰ προσήνεγκε. ταῦτα νῦν ἔτι τὰ ἱερὰ Θηβαῖοι φυλάττουσι καὶ πρὸ Ἡρακλέους ἑορῇ θύουσι Φαλινθιάδι πρώτῃ.

At Thebes Proetus had a daughter Galinthias. This maiden was playmate and companion of Alcmene, daughter of Electryon. As the birth throes for Heracles were pressing on Alcmene, the Fates and Eileithyia, as a favour to Hera, kept Alcmene in continuous birth pangs. They remained seated, each keeping their arms crossed. Galinthias, fearing that the pains of her labour would drive Alcmene mad, ran to the Fates and Eileithyia and announced that by desire of Zeus a boy had been born to Alcmene and that their prerogatives had been abolished. At all this, consternation of course overcame the Fates and they immediately let go their arms. Alcmene's pangs ceased at once and Heracles was born. The Fates were aggrieved at this and took away the womanly parts of Galinthias since, being but a mortal, she had deceived the gods. They turned her into a deceitful weasel, making her live in crannies and gave her a grotesque way of mating. She is mounted through the ears and gives birth by bringing forth her young through the throat. Hecate felt sorry for this transformation of her appearance and appointed her a sacred servant to herself. Heracles, when he grew up, remembered the favour she had done for him and made an image of her to set by his house and offered her sacrifices. The Thebans even now maintain these rites and, before the festival of Heracles, sacrifice to Galinthias first.

(Antoninos Liberalis, Metamorphoses XXIX, as translated by Francis Celoria.)

The mention of Hekate here is very interesting, and this leads me to my own conclusion concerning Apollon Smintheus, which ties into a theory I expressed before.

Now, one the one hand, Apollon and Hekate have a sort of connection: Hekate means "from afar," and is the feminine form of a common epithet of Apollon (e.g. as a marksman); on the other hand, the two couldn't be more opposite: Apollon is the lord of light, while Hekate is the lady of darkness; Apollon is heavenly, while Hekate is chthonic; Apollon is associated with unity (indeed, the Neopythagoreans derived his name from ἁ-πολλόν "not many"), while Hekate is associated with multiplicity (always appearing triform). From a Neoplatonistic view, one gets the sense of Apollon guiding upwards and Hekate dragging downwards.

I think all these stories give us another angle on the same thing: Apollon is the god of mice, Hekate the goddess of weasels, and weasels eat mice. Since Apollon is the god of the mysteries, we might consider mice as his initiates; similarly, since Hekate is the goddess of magic, we might consider weasels to be magicians. Thus from these symbols it is very little wonder that most of the philosophers warned their students away from magic so vociferously: at that early stage, fired with enthusiasm for things spiritual, they could very easily be consumed by it and drawn to use spiritual means for material ends. As Lucius found out in the Golden Ass, of course, this leads nowhere.

On the other hand, Homer tells us that Apollon is also the god of falcons, which isn't a surprise to anyone who's been following my Horos series:

ὣς ἄρα οἱ εἰπόντι ἐπέπτατο δεξιὸς ὄρνις,

κίρκος, Ἀπόλλωνος ταχὺς ἄγγελος: ἐν δὲ πόδεσσι

τίλλε πέλειαν ἔχων, κατὰ δὲ πτερὰ χεῦεν ἔραζε

μεσσηγὺς νηός τε καὶ αὐτοῦ Τηλεμάχοιο.

As he was saying so a bird flew towards him on the right,

a falcon, the swift messenger of Apollon; and with its feet

it plucked a pigeon it was holding, and feathers fell to the ground

between Telemakhos and his ship.

(Homer, Odyssey XV 525–8, as translated by yours truly.)

If the association of mice with initiates and weasels with magicians is correct, then falcons are surely heroes: those who have mastered the mysteries and soar on the wings so given.

I should also note, of course, that falcons eat weasels.