An Interpretation of Cupid and Psyche

Sep. 4th, 2023 10:50 am

As an exercise, I have attempted an interpretation of each point in the myth of Cupid and Psyche. I am starting, here, from the knowledge that Apuleius was both an initiate of the Mysteries (those of Dionysus and Isis for sure, and possibly others) and a Platonist. Further, it seems to me that since versions of the tale of the Golden Ass are known to predate Apuleius, but the fable of Cupid and Psyche is not, that Apuleius intentionally retold a popular story but inserted a fable of his own construction in order to more widely disseminate the Mysteries while not breaking his oaths of silence; but more than that, it's plausible that he gave the fable a firmly Platonist slant which may not have been present in the original Mystery teachings.

However, some caveats are in order: I am a half-baked scholar at best, I have not studied Plato very deeply, and neither am I very familiar with the middle Platonists besides Apuleius and Numenius. I have relied heavily on Plotinus in my unpacking, but this almost certainly contains a number of assumptions that Apuleius would not have made, and I am unfortunately blind to those. Thomas Taylor also gives an interpretation of the fable, but he departs even more widely, being firmly wedded (as in all things) to Proclus. In some instances I have agreed with him, and in others I have disagreed; but while I figure we're both correct in the broad strokes, we probably both fall short of apprehending the fable exactly. In any event, right or wrong, this is an attempt to understand the myth by what it meant to the Hellenistic Platonists, and it does not necessarily represent my own personal beliefs.

I have placed the interpretation below a cut, as it is lengthy and in case you wish to avoid it (for example, if you want to attempt your own study without contamination).

(The numbers of each section do not correspond to my previous post: I have grouped related points together.)

I. A king and queen have three beautiful daughters. The youngest and loveliest daughter is named Psyche.

This first part of the story doesn't technically take place—it happens "before the soul exists", but souls are eternal—but we are bound by time in our storytelling, so this part of the story exists for narrative expedience. In any case, the king, queen, the city they rule, etc., play no meaningful part in the story.

Properly speaking, souls are indivisible and do not have parts; but nonetheless the three sisters collectively represent the three faculties of an individual human soul as recounted in the Republic: the elder sisters are Desire and Fight, and Psyche is Reason. They are the daughters of a king because souls are inherently noble, and they are beautiful because souls are indescribably beautiful and infinitely precious. Psyche is the youngest because Reason matures the slowest of the three (or else the soul wouldn't descend into matter at all), and Psyche is the loveliest because Reason is the crown of the soul. Psyche is also used to represent the entire soul in the myth.

II. The multitude worships Psyche instead of Venus.

Venus represents the principle of beauty and harmony in the cosmos, a facet of the Intellect, rather than a god proper (who would otherwise be the highest kind of soul).

The multitude represents matter, the limit of division, a falling away from divinity (which is, ultimately, unitary). The multitude worships Psyche since the soul is necessary to give form to matter. (To give it form is to give it beauty, though the material beauty a soul imparts is as pale an imitation of true Beauty as Psyche is a pale imitation of Venus.)

III. Venus is enraged and summons Cupid to punish Psyche by causing her to fall in love with the most wretched of men.

Cupid is love: in this context, the soul's action, it's motion, it's life. He is the son of Venus because beauty (whether true Beauty or material beauty) provokes love. For the soul to fall in love with the most wretched of men is for the soul to desire to go as far away from the light of the One as possible, which is another way of saying to lose itself in matter as deeply as it can.

Venus' angry tirades are merely for comedic effect: division is contrary to the nature of divinity (and harmony, for that matter). Nonetheless, whether or not the fall of the soul is a punishment for sin or merely its involuntary nature was a topic of debate among the philosophers: Apuleius seems to take the "sin and punishment" side of things; Plotinus, at least, was ambivalent about it.

IV. Cupid is enchanted with Psyche, pricks Himself with one of His arrows, and resolves to marry her.

Life attaches itself to the soul. This very life is the remembrance of and upward tendency towards divinity that each soul contains within it; this upward tendency counters its downward path towards matter, preventing it from falling too quickly or too completely, and is also how it returns upwards again.

We're going to see a lot of being pricked by Cupid's arrows in this story. It always means to fall in love with the next thing one sees.

V. Psyche's sisters are happily married. Psyche, worshipped only from afar, sorrows her loneliness and hates her beauty.

The soul is not naturally self-sufficient—only the Intellect is—but rather it needs to acquire this self-sufficiency through experience. Instead, just as matter clamors for the soul, the soul itself has a natural tendency towards division (and is thus pulled in both directions, up and down, which is perhaps we all are so confused all the time).

I think, also, that Desire and Fight are happy to foolishly rush ahead into things—Reason takes much longer to understand and make use of its powers. Hence, Psyche's sisters are active in their pursuits, yet Psyche herself is extremely passive for quite some time.

VI. Psyche is told in an oracle that she is to be wed to a monster fearsome even to Jove. Her family laments and her wedding is celebrated as if it were a funeral, but Psyche resigns herself to her fate. Psyche is left alone on a lofty mountain. Zephyr carries her to a richly decorated palace in a beautiful valley.

The soul is "born," coming into existence from the Intellect into the intelligible world, a beautiful and idyllic place made by divine craftsmanship.

VII. Psyche discovers that the palace is hers by marriage and is filled with servants which she can hear but not see. She enjoys the palace. Cupid and Psyche are illicitly wed. Cupid comes to Psyche every night, but always leaves before morning and Psyche never sees Him.

And life comes to the soul and it begins to desire. To the Neoplatonists, the goal for a soul is to be content with itself, and at first, Psyche is satisfied with such an arrangement. Her unseen servants and husband are a reference to the nature of the intelligible world itself: the soul does not have eyes or seeing organs, but knows its surroundings instantly and intuitively. Psyche, too, comes to love her unseen husband: this indicates a pure desire, without concern for outward appearance which appeals to the senses, but only for the essential nature of the thing loved.

VIII. Psyche's family is in mourning. Cupid warns Psyche against her sisters. Psyche sorrows her loneliness and begs permission to see her sisters and give them gifts. Cupid consents on the condition that Psyche tell her sisters nothing of Him and that she never attempt to look at Him. Psyche entertains her sisters at her palace and gives them lavish gifts. The sisters inquire after her husband, but Psyche keeps Him a secret. The sisters burn with envy and resolve to destroy her.

The other faculties of the soul, both less temperate and less simple than Reason, vie for control over the soul's activity. The soul is pulled in two directions, seeking both self-sufficiency and division.

IX. Cupid tells Psyche that she is pregnant, and again warns her against her sisters, saying that if she keeps Him a secret from them, the child will be divine; but if she reveals Him, the child will be mortal. Psyche rejoices.

The soul's action is how it produces: if the soul is turned inward, it's productions will be intelligible; but if the soul is turned towards division, it's production will be sensible (e.g. will be a body). (As we shall see, the child is Pleasure: but the turning of the soul indicates whether this is a spiritual Pleasure or a mere sensual pleasure.)

X. Psyche again entertains her sisters at her palace. The sisters again inquire after her husband, but Psyche keeps Him a secret. Psyche's sisters nonetheless deduce that she has married a god and burn with greater envy. Psyche's sisters convince her that her husband is a monster and urge her to take a lamp and a dagger in the middle of the night, look upon him, and slay him. Psyche is tormented by fear and worry.

Plato likens Reason to the leadership of a state: it is always in charge of the other faculties, but the clamoring of the other faculties can cause the leadership to make foolish decisions. So it is that Psyche's sisters cannot overpower her but can only cause mischief through bad counsel. Here the soul convinces itself that maybe, just maybe, sensual pleasures might be more desirable than a pure life in the intelligible.

XI. Psyche discovers her husband is Cupid and intentionally pricks herself with one of His arrows. Cupid awakens, sees that his wife has broken her promise, admonishes her, and takes flight. Psyche throws herself into a river, intending to kill herself, but the river carries her to a riverbank downstream. Psyche meets Pan. Pan advises her to cease attempting suicide, lay aside her sorrow, and instead assuage Cupid through worship.

This is the first circumstance in the story where Psyche takes action, rather than passively accepting what comes to her. But oh!—a foolish action! The soul abandons its pure love of unseen things for the outward love of beauty, trading its intelligible desire for sensible desire. Consequently, the soul loses itself in the sensible world, constructing a body for itself in order to fulfil its sensible desires. (There was a debate among the philosophers on whether the soul literally travels into the physical body. Plotinus, at least, says that the soul in fact remains in the intelligible world but is asleep, in a sense, and completely bedazzled by the sensations of its body and insensate to what is right around it.) The river represents her transition into sensory experience, being born into her first body of many. Cupid flees, indicating the Psyche no longer can return to her previous home—only the memory of it lingers and beckons her upward again.

Pan represents the soul of the world. His advice to Psyche is what the sensible world is here to teach us: cease your descent, turn your eyes upward to the place you have left behind, and remember.

XII. Psyche wanders. She chances to meet her sisters, one after the other, telling them that her husband was Cupid, and that, as punishment for her attempted murder, banished her and would wed the sister, instead. Each sister, blind with lust, rushes to Cupid's palace and dies.

The wandering is the soul's long and hard experience in the world, reincarnating in body after body. In time, the soul finally learns to place its faculties all under the control of Reason, "killing" the desires and passions.

XIII. A seagull gossips Cupid and Psyche's story to Venus. Venus is scandalized. She berates Cupid and locks Him in a room, but is prevented from punishing Him further through the intervention of Ceres and Juno. Psyche wanders. She eventually chances upon a temple of Ceres and a temple of Juno, one after the other, and beseeches aid. Ceres and Juno each refuse, but do not detain Psyche.

Venus is sometimes described as the Mother of Necessity (for example, in the Orphic Hymn)—this is because, in order for the cosmos to be an ordered and harmonious whole, actions often have necessary consequences. Venus locking up Cupid is, here, a representation that the soul's descent is "locked in" until the necessary consequences of its actions are brought to completion—that is, until its karma is paid.

I think that Ceres is a representation of mundane deities and that Juno is a representation of celestial deities; that they placate Venus is descriptive that while circumstances here in the sensible world are difficult, they are not devoid of Providence. That Psyche approaches them shows that, after submitting itself to Reason, the soul appropriately turns itself to divinity in seeking release from the cycle of reincarnation. Nonetheless, while divinity supports the soul's efforts, it may not intervene directly: the soul must save itself from the consequences of its actions.

XIV. Venus summons Mercury to proclaim to all that She has placed a bounty on Psyche. Psyche hears of it and hastens to the temple of Venus. Venus taunts and torments Psyche.

After a certain point in the cycle of reincarnation, the soul begins to hear a very insistent siren's song towards the spiritual—one can't help it and must pursue it at any cost, and the cost can be substantial (at least from a bodily perspective). This is, I think, what Mercury's proclamation, Psyche's hastening to the temple of Venus, and the torments she receives there represents: the soul has now placed itself at the service of divinity: that is, cosmic harmony.

XV. Venus assigns Psyche four tasks. The first is to sort a large heap of mixed grains under a severe time limit: Psyche is stupified by the enormity of the task, but a colony of ants take pity on Psyche and complete the task for her. The second is to collect fleece from a flock of violent sheep: Psyche attempts to drown herself in a neighboring river, but a reed takes pity on Psyche and advises her on how to complete the task safely. The third is to fill a jar from a Stygian spring guarded by fierce dragons: Psyche is petrified with fear, but an eagle takes pity on Psyche and fills the jar for her. The fourth is to take a box to Hades and ask Prosperine to fill it with some of Her beauty: Psyche climbs a lofty tower in an inept attempt to accomplish the task, but the tower advises her on how to complete the task safely, even amid traps laid by Venus, and she does so.

Now that the soul has set reason in charge and placed itself in the service of cosmic harmony, it begins to master the state it finds itself in. Each task is representative a domain of human endeavor the soul is to master: the grain is representative of self-sustenance and the soul is aided by the powers of earth (solidity, strength); the wool is representative of crafts of civilized life and the soul is aided by the powers of water (reflection, understanding); the spring is representative of social life and the soul is aided by the powers of air (communication, flexibility); and going to, and returning alive from, Hades is representative of life and death itself, and the soul is aided by the powers of fire (creativity, optimism).

This last task is especially interesting as it has a great many additional allegorical symbols in it. The unusual customs that must be followed represent the various spiritual capacities one must develop, be they mystical or magical. The many snares laid by Venus are the dangers of the misuse of spiritual capacities. Proserpine herself represents the Mysteries, and the box of beauty she gives to Psyche is philosophy.

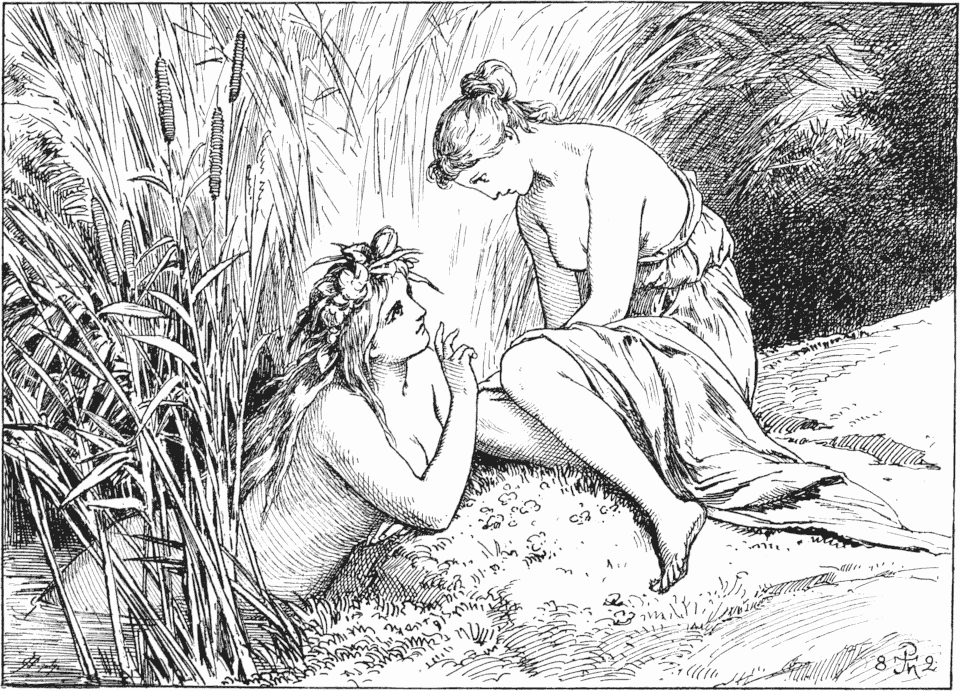

XVI. Anxious to be reunited with Cupid and hopeful of claiming a little of the beauty within, Psyche opens the box before delivering it to Venus; however, the box contains only death. Psyche dies. Cupid escapes confinement, puts death back into its box, and awakens Psyche with one of His arrows. Psyche delivers the box to Venus.

As Socrates says, the philosopher is, in fact, a disciple of death; by opening the box (representing philosophy), the soul dies to the body and is reborn into the spiritual.

What the soul loves—that is, what its action is directed towards—governs where its attention is. The soul's attention, when directed towards the sensible world, is what produces a body and is why the soul is completely invested in the body. But Cupid, here, is not the beautiful boy with the golden hair, but once again the pure, unseen being that Psyche was originally familiar with: Cupid reawakening Psyche with an arrow is the soul reawakening to true love, rather than the love of outward form: by turning it's attention away from the sensible world, the soul will no longer clothe itself in a body once its current one expires.

Cupid awakening Psyche is the point in the story where artists begin to depict Psyche as having little butterfly wings: she is semi-divine already, awaiting only the formality of living in the intelligible world. This is when the soul has finally paid off its "karmic debts" (as Cupid has escaped His room) and is free to take flight as soon as its last body ceases to hold it. But note that there is still a little work to be done, the last of the tasks to be completed, and the soul must finish it before it returns to its original estate.

XVII. Cupid pleads his case to Jove. Jove summons all the gods and legitimates Cupid and Psyche's marriage. Psyche is fetched to Olympus and given ambrosia, making her divine. A wedding feast is held.

Jove, here, is acting in the same capacity as Venus was earlier: the aspect of the Intellect relating to the harmony and order of the cosmos. Thus He tells Venus to relent in Her hostility towards Psyche, as the soul has returned to a state of purity.

The wedding being legitimated demonstrates the maturation of Psyche. At first she loved Cupid, not by choice, but because she was too innocent to know otherwise. The soul, through it's long and painful sojourn in the sensible world, now has the experience to understand and commit to its choices with their various ramifictions.

The wedding feast, of course, represents joy and celebration: not only of the soul itself, finally going Home, but of the many friends and relations that await it there.

XVIII. Psyche bears Cupid a daughter, whom they name Pleasure.

Even after it is restored to its eternal state, the soul continues to act, continues to produce. The overcoming of death is not the end of the story, rather just the beginning of it. Plotinus says that the world of soul is vast, much larger than the sensible cosmos: so big is it, that who can say what it is like to be there, and what it is we will be doing there? Whatever it is, though, being divine and closer to Good, it is certain that Life there is happier than life here.

Some random thoughts

Date: 2023-09-05 02:17 am (UTC)III. Karma for overemphasising reason is a love for the ugly?

IV. Falling in love with reason will lead to a lot of trouble later on...

V. Reason without action is isolating?

VI. Love as rebirth?

VII. 'Can hear but not see' = reason can't fathom love

IX. Try to explain love and you will kill it.

XI. The reason choosing to love kills love?

XII. Reason can only kill the other faculties through trickery?

XVI. The search for beauty kills reason?

XVIII. Uniting love with eternal reason creates pleasure?

Re: Some random thoughts

Date: 2023-09-05 03:42 pm (UTC)no subject

Date: 2023-09-10 02:34 am (UTC)According to Plotinus (and Taylor, as it happens), it seems that Psyche's descent from the lofty mountain to the beautiful valley is, indeed, a "first" descent of the soul; from there it can stop, or it can proceed to descend further and further down as far as it will.

Now is not a good time for editing this, but I'll have to revisit once I've reread and reconsidered this more thoroughly...

no subject

Date: 2023-10-18 08:49 pm (UTC)