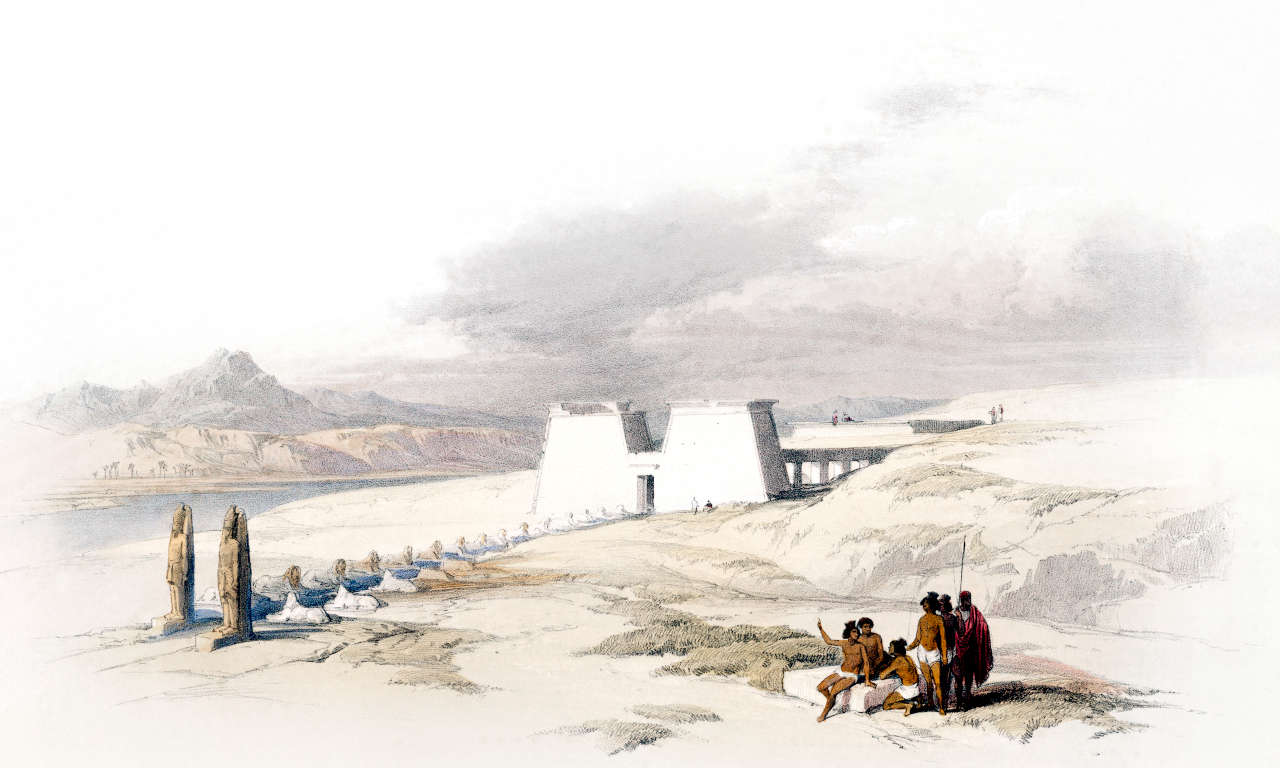

Following the Avenue of the Sphinxes

Jun. 9th, 2025 03:23 pm

I have no idea what the Egyptian sphinx represents—best guess is that it was originally just a lion, but some narcissistic jerk re-sculpted his face onto it—but the Greek sphinx, at least, is simply the riddle, the puzzle, the koan personified: it entices you in with it's pretty face and soft breasts, but once you get close, it sinks its claws into you. (In fact, the word Σφίγξ "sphinx" is from the Greek σφίγξω "I will hold tight.") With that image, an entire avenue of sphinxes seems a frightening prospect, and yet here I am, traipsing down just such a path...

A while back I noted that there were two major Greek myth cycles, the "city myth" and the the "hero myth." The first of these (exemplified by the two great cycles of the Heroic age, Thebai and Troia) follows seven generations of kings as they found a city, the city's royal line splits, the main branch fails (due to assaults from foreigners ultimately caused by a divine curse), while the secondary branch moves on to found a new city. On the other hand, the "hero myth" (exemplified by the Horos myth and the Orestes branch of the Epic Cycle), describes the structure of the world that we inhabit and describes what we can do about it; it is meant to be an example to prospective initiates, just like Athenaie says:

ἢ οὐκ ἀίεις οἷον κλέος ἔλλαβε δῖος Ὀρέστης

πάντας ἐπ’ ἀνθρώπους, ἐπεὶ ἔκτανε πατροφονῆα,

Αἴγισθον δολόμητιν, ὅ οἱ πατέρα κλυτὸν ἔκτα;

καὶ σύ, φίλος, μάλα γάρ σ’ ὁρόω καλόν τε μέγαν τε,

ἄλκιμος ἔσσ’, ἵνα τίς σε καὶ ὀψιγόνων ἐὺ εἴπῃ.Or haven't you heard what kind of renown noble Orestes gained

among all men when he avenged his father by murdering

that weaselly Aigisthos, who killed his illustrious father?

Likewise you, my friend—for I see that you are very handsome and well-built—

be courageous! so that even those yet to come may speak well of you.(Athenaie, in the guise of Mentes, exhorting Telemakhos. Homer, Odyssey I 298-302, as translated—hopefully not too badly!—by yours truly.)

This is, in fact, why Horos never goes to Bublos or why Orestes never goes to Troia: they are drawing on the lessons of the "city myth" in order to determine their own path. The city is an abstraction or teaching to them, the stories of those who went before, rather than a lived experience. In fact, it suggests that the city is a place they want to avoid, a source of trouble! Because of this, it seems rather important to make sense of what the city is and what it means, but I've been in difficulty doing so. I hit upon a potential angle on it, though, that I thought might be worth walking through.

I recently mentioned the Ra Material in reference to Teiresias (himself a part of the Thebaian city myth), and while pondering this, I realized that "Ra's" metaphysics dovetails neatly with the city myth, with "Ra's" seven degrees of consciousness corresponding very well with the seven generations of kings; under this interpretation, the city myth describes the unfolding of the Cosmos from Source to Source, while the hero myth, situated at the end of it, tells us what we can do about it right now, today, and what we can expect to happen to us if we try.

As a disclaimer and a reminder, I'm pretty skeptical of channeled texts (and doubly so of anything "New Age") for a few reasons: first, I have a pretty strong anti-modernity bias; second, most people are incapable of reaching up to the aither to channel angels, and even if they can, it can be very difficult to tell since daimons "know how to tell many convincing lies;" third, the channelled material always reflects the biases of the person doing the channelling, and if one isn't personally close with them, it can be very difficult to correct for these; and fourth, the "New Age" seems to largely presuppose a worldview I don't adhere to, and involve wish-fulfilment fantasies which I'm not interested in. So this material needs to be taken with salt; please consider this post merely an attempt to expand upon my prior exploration of Teiresias in order to make a more comprehensive evaluation of the model possible.

Perhaps I should start by describing "Ra's" view of the development of consciousness. (Or attempting to, it is not perfectly clear to me, so take this as a sketch.) Consciousness is analogized as a vibration, and this continuum of vibration is discretized into seven degrees of consciousness, just like how we break up all the possible vibrations of the air into a scale of seven notes or all the possible vibrations of the visual spectrum into seven colors. Since souls are just a vehicle for consciousness, we inherently possess the capacity to vibrate in any harmony of frequencies, at least potentially; but in practice, one has to "climb the scale" a bit at a time, from lowest vibration to highest vibration:

Red, which relates to being, and is the consciousness of "inanimate" objects.

Orange, which relates to growth and movement, and is the consciousness of plants and animals.

Yellow, which relates to social identity, and is the consciousness of humans. Being the vibration of identity, it is the first properly "individual" degree: red and orange are "herd" or "group" consciousness, while yellow consciousness is individual (at least once sufficiently developed).

Green, which relates to love, and is the consciousness of lower daimons. Love is polarized: one may give love (compassion) or take love (selfishness), and thus green consciousness is dual in nature.

Blue, which relates to communication and wisdom, and is the consciousness of higher daimons, though it is also (being the lowest vibration not subject to mortality) where we resonate with after death. Blue retains the polarized nature of green; the positive pole is the collective search of understanding (collaboration), while the negative pole is the individual search of understanding (hoarding knowledge).

Indigo, which relates to universality, and is the consciousness of angels. Unlike green and blue, indigo is not meaningfully polarized, because of the nature of universality; negatively-polarized individuals, having mastered wisdom, come to understand this and reorient themselves positively as they endeavor to comprehend the All.

Violet, which is related to transcendance and unity. This is, in a sense, rejoining the All and moving on to a new "octave" of existence, in which one co-creates the universe as and with God. (At least, apparently: "Ra" claimed to be of indigo consciousness, themselves, and claimed only secondhand knowledge about violet consciousness from its own teachers.)

Apparently souls usually ascend as groups: that is to say, the group of what we now call "human souls" all passed through the red stage more-or-less together, then the orange stage more-or-less together, and are now working through the yellow stage more-or-less together. ("Ra" says the reason why the earth is such a mess is that, apparently unusually, humans aren't developing consistently: a few are polarizing positively, a few others are polarizing negatively, and the vast majority aren't polarizing at all. Evidently conditions are much smoother in the common case where the group develops together.) There are uncommon exceptions to souls developing as a group, however: some people are souls of a higher degree, who incarnate as humans in order to teach and guide; while, conversely, some few human souls "jump the tracks" and, through spiritual practices or divine support or sometimes even by accident, behold God naked and become able to ascend separately from the rest of their group.

I think that's enough about "Ra's" metaphysics to get on with. So far so good, and other than the emphasis on soul-groups, isn't too distant from Empedokles or Plotinos.

As for the city myths, there is, unfortunately, no one good source remaining for either of them. I'd like to look at Troia today, partly because I looked at Thebai last time and partly because the Epic cycle is by far the more familiar to me. The outlines of it's history can be more-or-less cobbled back together from bits and pieces in the Iliad and Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite (which I trust) and the Library (which is my preferred fallback when a reliable source isn't available). Here is a sketch at describing the seven generations, with citations:

Dardanos, the favorite mortal son of Zeus, founded Dardania at the foot of Mt. Ide. [Il. XX 215-8, 301–5.]

Erikhthonios, the son and successor of Dardanos, "became the richest of all men" with a herd of three thousand mares. Boreas mated with some of these mares in the form of a black stallion, adding twelve semi-divine horses to Erikhthonios's herd. [Il. XX 219–29.]

Tros is the son and successor of Erikhthonios, renaming the kingdom (but not the city) of Dardania after himself. [Il. XX 230, Lib. III xii §2.]

At this point the royal line splits three ways, as Tros has three sons: Ilos, Assarakhos, and Ganumedes. All three are described as faultless. Ilos goes to Phrygia; he wins a prize of fifty men and women; following an oracle's instruction, he follows a dappled cow to the hill of Ate; he asks Zeus for a sign; he is given the Palladium; and he founds Ilios on the spot. Assarakhos, meanwhile, simply succeeds to the throne of Dardania. Ganumedes, finally, being peer of the gods and most beautiful of mortals, is spirited away in a whirlwind to be the immortal, ageless cupbearer of Zeus; Tros is grieved by his son's disappearance until Zeus sends Hermes to tell him what has become of him and give him divine horses. [Il. XX 231–5; HH 202–17; Lib. III xii §3.]

Laomedon is the son and successor of Ilos, and also described as faultless. Kapus is the son and successor of Assarakhos. [Il. XX 236, 239.]

Priamos is the son and successor of Laomedon; he is the final king of Ilios, since while Zeus loves Priamos and his city, he withdraws his favor from Priamos's line and gives it to Aineias. Ankhises is the son and successor of Kapus; he was seduced by Aphrodite, but not made immortal; and he secretly bred his mares to the divine horses of Laomedon (descendants of those ransomed for Ganumedes), thereby stealing their bloodline. [Il. IV 44–9, V 265–72, XX 236, 300–8; HH.]

Hektor is the son and heir apparent of Priamos, but is killed in battle by Akhilleus. Aineias is the son and successor of Ankhises; he is the son of Aphrodite; he is most pious and beloved by the gods; and he escapes Ilios and refounds it after it is sacked. [Il. II 819–21, XX 293–308, XXII; HH.]

Now, let's synthesize these two models. I don't think this is too difficult! The seven kings can obviously be linked to the seven degrees of consciousness, with the line of descent showing the progression of consciousness (e.g. orange follows red just as Erikthonios follows Dardanos), and with the split among the sons of Tros showing the split in polarization at the green level of consciousness (e.g. just as, after Tros, the Troad has two kingdoms, Dardania and Ilios, so too does consciousness have two polarities after yellow). Everything else falls out naturally from there.

Mt. Ide (traditionally from ἴδη "woods," as in a place of material to harvest and work with) is the world-axis or ladder of consciousness, which is why Zeus sits atop it and watches all. The hill of Ate (Ἄτη "blindness, recklessness") is presumably where Zeus threw her after Hera tricked him into recklessly making Iphikles king rather than Herakles (cf. Il. XIX 91–136), clearly a place where a lack of foresight makes one deviate from the intended course. Dardania (apparently related to the onomatapoeic δάρδα darda "bee," like "bumble" in English, and an appropriate name for cooperation, as a hive of bees work together for the good of all) is the positive polarization of consciousness, while Ilios (which Ilos, of course, selfishly named for himself) is the negative polarization of consciousness, distant from Ide but still in sight of it (as one can never really escape divinity).

Dardania is founded by Dardanos at the foot of Ide since red consciousness is foundational, inherently positive, and where everything begins; while Ilios is founded by Ilos on Ate since green consciousness is the first that can be negatively polarized (though doing so is short-sighted). Nonetheless, each of Tros's three children are described as ἀμύμονες "without blemish," because all is one, so to love others and to love self are both to love God. However, Tros has a third faultless son: Ganumedes; Xenophon's Socrates (Symposium VIII xxx) makes the case that Ganumedes was beautiful in soul, and I likewise think that Ganumedes is a mythic representation of how peculiarly virtuous souls can short-circuit the usual path of growth through intensive self-development and/or devotion to divinity. Zeus withdraws his favor from Priam because negative polarization halts at the indigo level (thus ending the line of Ilos), and Hektor dies in battle because it is not possible for a negative polarization to transcend. Aineias refounds Ilios because the result of returning to the One is to co-create the next "octave" of consciousness.

Homer goes to particular lengths to talk about horses (maybe they should have called him Φίλιππος Phillip "horse fancier"), so these must be noteworthy for some reason. I suppose that while the kings represent the levels of consciousness in general, the horses must represent their property; that is, specific individuals or groups of individuals within those levels of consciousness. Perhaps the wealth of Erikhthonios indicates the vast speciation of the natural world, while the offspring of Boreas ("the North Wind") indicates that only some of the many species of animals are judged desirable enough to become vessels of the yellow level (e.g. are imbued with "breath" or "wind," that is, individual soul); perhaps the horses Zeus gifts to Ilos indicate that while some beautiful souls may leave the group, the group is not neglected, but is in fact given support in recompense for their loss in order to maintain balance; that Ankhises breeds his horses with the descendents of these perhaps suggests that these beautiful souls join groups of the indigo level ("go to be with the angels"). These kinds of things aren't really discussed in the Ra Material so far as I recall, though, so this is all not-terribly-deep guesswork based strictly on the symbolism in the myth.

A few miscellaneous notes from while I was working my way through all this:

I have long wondered why Homer is so very down on Aphrodite; she seems to me to be among the nicest of the gods. One nice thing about this interpretation of the city myth is that it makes sense of this. Aphrodite is love, and loving mode of consciousness—green—is where polarization takes place; since Ilios is the negative polarization, which is ultimately incapable of returning to the source, this is the reason for the city's downfall. In fact, that Zeus refuses to adjudicate the apple to any of the goddesses indicates that God has given us free will to choose our paths; that Paris has to choose between Aphrodite (= love = green?), Athene (= wisdom = blue?), and Hera (= universality = indigo?) indicates that these are the levels affected by choice of polarization; that Paris chooses Aphrodite for reasons of self-gratification reinforces the recklessness (ate) of the negative polarization in general.

I'm not really prepared to do a deep-dive on the Thebaian myth yet, but while we're talking about sphinxes, it's worth noting that Oidipous, being of the fifth royal generation, would, by this theory, be of the blue, or wisdom, degree of consciousness. This makes his solving of the sphinx's riddle—a test of wisdom—pretty appropriate!

If you'll recall in the Horos-myth, I likened Thoth to "experience," the reason or purpose behind climbing the ladder of consciousness: so God-in-part can come to know part-of-God. Thoth is married to Maat, the "necessity" of this occurring. It is noteworthy that the child of Thoth and Maat is Seshat "scribess," who is depicted with two cow horns and a seven-petalled flower above her head. It is plausible to me that "scribess" is a reference to consciousness being that which observes and records (cf. Od. XI 223–4) and the seven-petalled flower is indicative of the seven modes of consciousness here described:

𓋇

This would, of course, presuppose that "Ra" is correct in saying that they influenced the development of Egypt with their teachings.