In Isis and Osiris III, Plutarch exhorts his friend Clea, who has just recently become an initiate, to deprecate outward forms and instead cultivate the mysteries in her heart, because

it is a fact, Clea, that just like having a beard and wearing a coarse cloak does not make one a philosopher, neither does dressing in linen and shaving one's hair make one a votary of Isis; rather, the true votary of Isis is the one who, when they have legitimately received what is set forth in the ceremonies of these gods, uses reason in investigating and in studying the truth contained therein.

And this is exactly what makes the mystery cults so foreign of a religious sensibility to us, today: they didn't proselytize, they taught no dogma, and they enjoined silence upon their initiates, so that those initiates were forced to continually contemplate the symbols in their hearts and develop their own personal meaning from them. I think we've had ample lesson, measured in blood, of the dangers of dogma and the practical wisdom of this approach over the last millennium, but I think the real reason the Egyptian priests instituted this approach is that one only grows by making effort. The point of the mysteries isn't to cleverly find the right answer to a test; it is to continually push against them and thereby develop meaning within one's own soul. In that sense, it doesn't matter what one's understanding of the mysteries ends up being, so long as one is ever attempting to refine it.

Because of that, it was foolish of me to get sidetracked; however, it proved valuable nonetheless, since by going back to the beginning, I think I've found a more profitable avenue to explore. It is one that I hinted at previously, but actually taking the time to investigate it seriously has taught me a lot, and I will endeavor to communicate what I've learned as clearly as I can.

(But, of course, be warned that in doing so I may be robbing you of finding your own meaning by pursuing the course I've laid out! In studying and contemplating my way through the myth, I've been of two minds whether or not to post what I've learned: the gods of the mysteries castigated Numenius for revealing their secrets, but seem to have regarded Plotinus most highly for doing the same. In the end, for various reasons, I've opted to proceed; but please exercise judgement in reading on if you wish to follow the old paths for yourself! For whatever it's worth, though, I am in all of this only following antecedents of my own, and joining myself—as a very weak link indeed—in that golden chain which binds heaven and earth: if that extra couple inches puts it within reach of anyone, and it doesn't break when they grab ahold, then I consider it to have been worth the effort!)

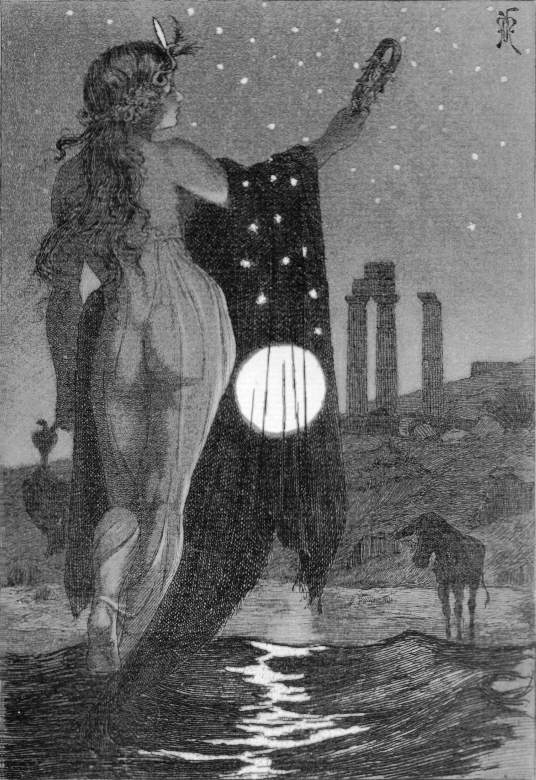

The ancient Egyptians held a tradition that their priests looked at the heavens with awe and reverence, and through much study of them came to learn of the gods underlying the Sun and Moon, whom they called Osiris and Isis, respectively (Manetho, Epitome of Physical Doctrines; Diodorus, Library of History I xi; the correction "underlying" from Pseudo-Plutarch, Stromateis). Over time, the understanding of these gods deepened, and the priests wished to codify it so that it might better be passed on, and so they instituted the mysteries in order to do so while still making their students work for their understanding. These were either first or most successfully instituted at the great temple of Heliopolis (modern Cairo), but they soon spread throughout Egypt, Assyria, and the Mediterranean, evolving as they went (Pseudo-Lucian on the Syrian Goddess II).

A couple thousand years later, a youth from the island nation of Samos, named Pythagoras, was very devoted to learning and went to study under the greatest Greek mind of the time, Thales of Miletus. Thales taught him everything he could, but finding the youth unsatisfied, urged him to continue his studies in Egypt. Samos was an ally of the Black Land, so Pythagoras secured a letter of introduction from his king, Polycrates, and went to pharaoh Amasis II, asking to learn from their priests. The pharaoh assented and sent Pythagoras to the priests of Memphis; but they, neither wishing to disobey the pharaoh nor initiate a foreigner, passed him into the care of the priests of Thebes (modern Luxor); who in turn passed him into the care of the priests of Heliopolis; who, having nowhere else to send him, instead enjoined him with extreme austerities, hoping that he would become discouraged and leave. Pythagoras performed those austerities so readily, however, that he won their admiration and finally became an initiate. He eventually established a sort of guild, the Pythagorean brotherhood, which served as a vehicle for teaching Pythagoras's interpretation of the mysteries: while he almost certainly introduced innovations (especially regarding the use of numbers), on the whole it appears to have been fairly faithful, and maintained the strict code of secrecy that the mysteries demanded. (Plutarch, Isis and Osiris X; Diogenes Laertius, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers VIII i §3; Porphyry, Life of Pythagoras VII–VIII.)

A couple generations later, a youth from Acragas in Sicily (modern Agrigento), named Empedocles, was very devoted to learning and went to study under the Pythagoreans. He wrote a very famous poem, after which he was expelled from the brotherhood under the charge of revealing their mysteries in writing (Diogenes Laertius, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers VIII ii §2). Because of this, and because his poem, like the mysteries, concerns the descent and reascent of the soul, it seems that his poem was a more-or-less faithful discussion of them and that it is likely a fruitful place to look for keys to unpacking the mysteries.

Alas, scarcely a tenth of Empedocles's poem survives to our time, mere scraps and tatters quoted by ancient commentators. (There is perhaps no other single work from antiquity which I wish we possessed complete today!) But because we have so little of it, we will be forced to tread tentatively and consider what the ancient commentators say in order to attempt to sketch Empedocles's worldview.

After Plutarch recounts the myth of Isis and Osiris, he considers the myth from various angles and gives Clea different tools to try and reason about what it may mean. In the second of these considerations (XXV ff.) he explicitly relates the wandering of Isis to Empedocles's poem, quoting him concerning the exile of souls:

ἔστιν Ἀνάγκης χρῆμα, θεῶν ψήφισμα παλαιόν,

ἀΐδιον, πλατέεσι κατεσφρηγισμένον ὅρκοις·

εὖτε τις ἀμπλακίῃσι φόνῳ φίλα γυῖα μιήνῃ

[...] ἐπίορκον ἁμαρτήσας ἐπομώσει

δαίμονες οἵτε μακραίωνος λελάχασι βίοιο,

τρίς μιν μυρίας ὧρας ἀπὸ μακάρων ἀλάλησθαι,

φυόμενον παντοῖα διὰ χρόνου εἴδεα θνητῶν

ἀργαλέας βιότοιο μεταλλάσοντα κελεύθους.

Αἰθέριον μὲν γάρ σφε μένος Πόντονδε διώκει,

Πόντος δ' ἐς Χθονὸς οὖδας ἀπέπτυσε, Γαῖα δ' ἐς αὐγάς

Ἠελίου φαέθοντος, ὁ δ' Αἰθέρος ἔμβαλε δίνῃς·

ἄλλος δ' ἐξ ἄλλου δέχεται, στυγέουσι δὲ πάντες.

τῶν καὶ ἐγὼ νῦν εἰμι, φυγὰς θεόθεν καὶ ἀλήτης,

Νείκεϊ μαινομένῳ πίσυνος. [...]There is an oracle of Necessity, an ancient decree of the gods, eternal, sealed with broad oaths: if one of the daimons who are heir to long life stains his dear limbs with blood or perjures himself through his misdeeds, then he shall wander apart from the blessed for thrice ten thousand seasons, being born meantime in all sorts of mortal forms, changing one bitter path of life for another. For mighty Aither pursues him Seaward, and Sea spits him forth onto the threshold of Earth, and Earth casts him into the rays of the blazing Sun, and Sun into the eddies of Aither, each receiving him in turn, all hating him.

I, too, am now one of these: a fugitive from the gods and a wanderer, at the mercy of raging Strife.

Teaching the citizens of Akragas that we humans are exiled divinities and urging them on the path of return appears to be Empedocles's primary purpose in writing his poem. In support of this, he spends quite a bit of time on metaphysics, describing that there are exactly six primary divinities (Hippolytus, Refutation of All Heresies VII xvii; Simplicius, Commentary on Aristotle's Physics), four "roots" and two "forces" which cause those roots to combine and disperse in various ways to produce all we see around us, even all other gods:

τέσσαρα γὰρ πάντων ῥιζώματα πρῶτον ἄκουε·

Ζεὺς ἀργὴς Ἥρη τε φερέσβιος ἠδ' Ἀιδωνεύς,

Νῆστις θ' ἣ δακρύοις τέγγει κρούνωμα βρότειον. [...]

ἐκ τῶν πάνθ' ὅσα τ' ἦν ὅσα τ' ἔστι καὶ ἔσται ὀπίσσω,

δέδρεά τ' ὲβλάστησε καὶ ἀνέρες ἠδὲ γυναῖκες,

θῆρές τ' οἰωνοί τε καὶ ὑδατοθρέμμονες ἰχθῦς,

καί τε θεοὶ δολιχαίωνες τιμῇσι φέριστοι. [...]

καὶ ταῦτ' ἀλλάσσοντα διαμπερὲς οὐδαμὰ λήγει,

ἄλλοτε μὲν Φιλότητι συνερχόμεν' εἰς ἓν ἅπαντα,

ἄλλοτε δ' αὖ δίχ' ἕκαστα φορεύμενα Νείκεος ἔχθει.First, hear of the four roots of all things:

shining Zeus and life-giving Hera and Aidoneus

and Nestis, who wets the springs of mortals with her tears. [...]

From these all things were and are and will be:

sprouting trees and men and women,

beasts and birds and water-dwelling fish,

even long-living, most-exalted gods. [...]

And these never cease from constantly alternating,

at one time all coming together into one by Love,

and at another again all being borne apart by the hostility of Strife.

Most ancient commentators (following Plato and Aristotle) consider these in purely physical terms, hence the "classical elements" as we know them today. However, I think this is a mistake: Empedocles calls them first by the names of gods and only later refers to them by other names. (And in these he is not consistent: sometimes he calls Love, "Friendship," "Joy," "Harmony," or "Aphrodite;" Fire, "Light," "the Sun," or "Hephaestus;" etc. So he is certainly speaking of something beyond mere physical experience.) Every self-important smartass from ancient times to today (erm, including myself, oops) has their own opinion of how to associate the gods and the elements in order to fit their preconceptions, but the preponderance of ancient sources (e.g. Diogenes Laertius, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers VIII ii; Hippolytus, Refutation of All Heresies VII xvii; Stobaeus, Eclogues I x) tell us that Zeus is Fire; Hera, Earth; Aidoneus, Air; and Nestis, Water. Rather than continuing in my folly, I have endeavored to follow the tradition to see what it can teach me; while I initially found it confusing, in the end I think it makes good sense of Plutarch's myth.

Empedocles describes a process of the roots all, originally, being held together in a state of Love, but peeling off from each other, one at a time, under the influence of Strife. Hippolytus (Refutation of All Heresies I iii), in fact, describes that original Fire as the Pythagorean Monad, the original unity from which all arises from and returns to:

Empedocles came after [the Pythagoreans] and wrote a great deal about the nature of daimons too, how they dwell in and administer affairs all over the earth, being very numerous. He said that the principle of the universe is Strife and Love and that god is the intelligent Fire of the Monad and that all things are constructed from Fire and will be dissolved into Fire.

Thus, I think Empedocles's cosmology is, in fact, describing what the Pythagorean tetractys symbolizes: the step-by-step expansion of the cosmos from Fire to the physical world. Let's take a look at it for a moment.

In the past, I have used the tetractys to symbolize Plotinus's cosmology, but I think Empedocles's system is different: he has no conception of hypostases ("planes of being"), but rather all things (except the roots and forces) exist within the temporal cosmos, and are thus subject to the changes in that cosmos over time as Love and Strife give way to each other in turn. As far as I can tell, Empedocles never speaks of eternal things: he always calls gods and daimons δολιχαίωνες, "long-lived;" and this seems to me to match the Egyptian conception, since even the mighty Ra grew old and senile. Where Plotinus provides an ontological ordering of the One, the Intellect, Soul, and Nature, Empedocles calls his roots co-eval, and this too seems to match the Egyptian conception, since the Egyptian Bremner-Rhind papyrus says that the four gods come forth "in one birth." So because of all this, I think we are to see the rows of the tetractys as the unfolding of the cosmos in time rather than ontologically.

So, in the first row, all is joined in Love and there is only the Monad, the "intelligent Fire" in which all exists. In the second row, Strife has interposed herself a little bit and Fire has separated out from the other roots, producing the Dyad. (It is for this reason that Empedocles calls Fire "destructive Strife" (Plutarch on the Principle of Cold XVI), since it is the beginning of separation. Similarly, Plotinus calls the One, "Love," and the dyadic Intellect, "Strife" (Enneads V i §9).) In the third row, Strife's influence has increased and separated Air, producing the Triad. Finally, in the fourth row, Strife's influence has reached it's peak, causing Water and Earth to separate and produce the Tetrad. The tetractys ends here, but Empedocles says that eventually even this stage comes to an end, and the cosmos squishes back together under the increasing influence of Love. I think it is of peculiar interest that Water and Earth separate out into their pure forms simultaneously: this matches how, despite using a different model, Plotinus says that the Watery "lower soul" and Earthy body come into being simultaneously. Something curious about that is that while Earth is the heaviest and most dense root, at least one commentator (Philo of Alexandria, On Providence) says that Empedocles says that the roots separate out in the order of Fire, then Air, then Earth: Water, due to its nature, just sort of passively takes up whatever space is left to it. (Perhaps this is why Empedocles calls Water "tenacious Love" (Plutarch on the Principle of Cold XVI), since it is the end of separation and the beginning of recombination.)

With all that in mind, let's take a fresh look at the myth.

I've mentioned previously that Apuleius tells us that there are three mysteries. However, I divide the myth into four: the theogony, the wandering of Isis, the separation and recombination of Osiris, and the contending of Horus and Set. I am doing this because I don't think the theogony is a mystery at all: Herodotus discusses it (Histories II iv), but (as an initiate) he is generally reticent concerning the mysteries (Histories II clxx ff.); Diodorus discusses it openly from multiple sources (Library of History I xiii) but elsewhere calls out secret teachings (Library of History I xxi); Manetho apparently discussed it, but as the high priest of Heliopolis, it seems unlikely that he would disclose its mysteries publicly; and it was apparently the explanation for and popular basis of the civil calendar.

Today, we're just going to revisit the first part, the theogony. As a part of taking a fresh look at it, I've gone ahead and revised my summary, placing it side-by-side with the equivalent Greek myth, which runs as follows:

| # | Plutarch, Isis and Osiris | Hesiod, Theogony; Pseudo-Apollodoros, Library |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | Sky and Earth have intercourse. | Kronos and Rhea have intercourse. |

| A2 | The Sun curses Sky so she cannot give birth on any day of the year. | Rhea gives birth to five children, but Kronos swallows them as they are born. |

| A3 | Isis (by Osiris) gives birth to Horus the Elder (in the womb of Sky). | Rhea secretly gives birth to Zeus. |

| A4 | Rhea "nurses" a stone to trick Kronos. The spilled milk forms the Milky Way. Kronos swallows the stone, thinking it Zeus. | |

| A5 | Thoth takes pity on Sky and takes a seventieth part of the Moon's light and makes it into five intercalary days so that Sky can give birth. | Gaia secretly raises Zeus. Zeus enlists the aid of Metis. Metis gives Kronos an emetic. |

| A6 | Sky gives birth to Osiris, Horus the Elder, Set, Isis, and Nephthys. | Kronos regurgitates the stone, Poseidon, Hades, Hera, Demeter, and Hestia. |

| A7 | Zeus battles Kronos for ten years, eventually defeating him and becoming king. |

This, I think, describes in mythic terms the process of cosmic expansion just as I did, above: Sky (Egyptian Nut, Greek Kronos) is the state of the cosmos where all is held together in a state of pure Love, while the Sun (Egyptian Ra, Greek Helios) is the force of Love itself, which keeps the roots together in the womb of Sky; while Earth (Egyptian Geb, Greek Rhea) is the opposing state of the cosmos where all is held apart in a state of pure Strife, while the Moon (Egyptian Iah, Greek Selene) is the force of Strife itself. This is reminiscent to me of what Proclus and Wolfram talk about: pure order (Sky, Love) and pure chaos (Earth, Strife) are both uninteresting, since order is too crystalline and static for any event to occur, while chaos is too random and mobile for anything to have being, and so it is their intercourse that produces the cosmos.

Then, the gods are born. I think it is quite easy to see the relationship of the Kronos myth and the Nut myth, and it is straightforward to equate Isis with Demeter; Nephthys (𓉠 nebet-hut, "lady of the house") with Hestia; and Horus with Zeus (though Zeus is properly Horus the Younger, who battles Set and becomes king, his birth is confabulated with Horus the Elder's), though the association of the other gods is a bit trickier. We can also see that the Kronos myth is self-contained, in a sense, covering also Zeus's fall to earth, growth in skill, and battle to become king, which is (as we shall see) what Horus's myth is about. It is also interesting, I think, how Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades are said to divide the sky (Air), sea (Water), and land (Earth) between them, which seems to echo Empedocles's roots somehow, though the relationship between gods and roots seems garbled. (At least, I can't make good sense of it.)

But this is a separate transmission of the myth into Greece from the one I want to talk about, which is Empedocles's. Ignoring Horus for a moment, since he is not a child of Sky and Earth, we have Osiris, Set, Isis, and Nephthys, explicitly ordered and yet also said to be born simultaneously. Given the order, I think it is easy to associate Osiris (Empedoclean Zeus) with Fire, Set (Empedoclean Aidoneus) with Air, Isis (Empedoclean Hera) with Earth, and Nephthys (Empedoclean Nestis) with Water; and since the gods are all "of equal age," their "births" on successive days represent not their coming into existence but their gradual separation under the influence of Strife. Because of Aristotle's influence, I think we moderns are used to thinking of the classical elements cyclically and "marrying" those of opposite qualities (bright Fire and dark Water, ephemeral Air and solid Earth), but the pairing of Fire with Earth and Air with Water, as here, has parallels in Plato's Timaeus and in the Geomantic tradition. It is also, of course, reasonable to associate Osiris with Zeus (as king), Set with Hades (as the one who snatches away souls from heaven), Isis with Hera (as the wife of Osiris/Zeus), and Nephthys with Persephone (as the begrudging wife of Set/Hades).

But if the roots are straightforward enough, we will need to make an effort on Horus since we have exhausted Empedocles's six principles, and I think the key to making sense of him is that there are two Horuses, an elder and a younger, which are certainly distinct (for example, they are shown side-by-side on the Metternich Stela), but their roles in myth are confused and conflated: in a sense, they are both two and one. Considering all this, I think Horus is one of Empedocles's daimons (indeed, the prototypal daimon) which has perjured themselves, is exiled from the gods, and after many trials is restored to their ranks. (Consider that his name in Egyptian, 𓅃 heru, is simply the word for "falcon," a bird which soars high up into the sky on thermals, a lovely image of a soul on its heavenly ascent.) Horus the Elder doesn't have any significant role in the myth, and I think he represents the passive potential of a soul, it's mere being or Platonic Form which exists within Osiris. After Strife has reached it's peak, Isis magically "draws from [dead Osiris] his essence" (that is, Horus the Elder) and using it gives birth to Horus the Younger, who is the actualization of that potential, the living soul which wills and acts.

Hesiod parallels Empedocles's "oracle of Necessity" in the Theogony (ll. 793–804):

ὅς κεν τὴν ἐπίορκον ἀπολλείψας ἐπομόσσῃ

ἀθανάτων οἳ ἔχουσι κάρη νιφόεντος Ὀλύμπου,

κεῖται νήυτμος τετελεσμένον εἰς ἐνιαυτόν·

οὐδέ ποτ' ἀμβροσίης καὶ νέκταρος ἔρχεται ἆσσον

βρώσιος, ἀλλά τε κεῖται ἀνάπνευστος καὶ ἄναυδος

στρωτοῖς ἐν λεχέεσσι, κακὸν δ' ἐπὶ κῶμα καλύπτει.

αὐτὰρ ἐπὴν νοῦσον τελέσει μέγαν εἰς ἐνιαυτόν,

ἄλλος δ' ἐξ ἄλλου δέχεται χαλεπώτερος ἆθλος·

εἰνάετες δὲ θεῶν ἀπαμείρεται αἰὲν ἐόντων,

οὐδέ ποτ' ἐς βουλὴν ἐπιμίσγεται οὐδ' ἐπὶ δαῖτας

ἐννέα πάντ' ἔτεα· δεκάτῳ δ' ἐπιμίσγεται αὖτις

εἴρας ἐς ἀθανάτων οἳ Ὀλύμπια δώματ' ἔχουσιν.For whoever of the immortals, who possess the peak of snowy Olympus, swears a false oath after having poured a libation to [the Styx], he lies breathless for one full year; and he does not go near to ambrosia and nectar for nourishment, but lies there without breath and without voice on a covered bed, and an evil stupor shrouds him. And when he has completed this sickness for a long year, another, even worse trial follows upon this one: for nine years he is cut off from participation with the gods that always are, nor does he mingle with them in their assembly or their feasts for all of nine years; but in the tenth he mingles once again in the meetings of the immortals who have their mansions on Olympus.

In those terms, I think descending Horus the Elder is the god sleeping as if in a coma in that first year, and ascending Horus the Younger is the god in exile for the nine following years. As we'll see much later, Horus the Younger is the Greek Apollo, who was himself exiled to earth and forced to serve Admetus for nine years before returning to Olympus, and so is the prototype or king of those daimons who have come before us, reascended, and now aid us in following them. (Small wonder, then, that Apollo is the special friend and helper of mankind!) Since the interplay of the two Horuses is at the core of the myth, we'll be talking about them much more as we proceed.

In addition to the sketching the cosmos, I think the order of the birth of the gods is a representation of their rank or pre-eminence: Osiris is of central importance all throughout the myth, initiating all the action in each stage of the story, and so is of first rank; Horus's ascent and victory is the outcome and purpose of the story, giving him second rank; Set's constant antagonism is responsible for both the fall of Osiris and the restoration of Horus, giving him third rank; Isis is the protagonist of part of the myth and the great initiator, giving her fourth rank; and poor Nephthys is hardly mentioned at all, taking the last place remaining. Ordering them in this way thus not only conceals an esoteric meaning (in the unfolding of the cosmos) but also has a practical exoteric meaning (in giving honors to the gods in the holiday calendar, and embedding their relative importance into folklore).

Finally, there is Thoth (Greek Hermes, Hesiodic Metis), who is representative of wisdom, skill, or experience, which is the very thing which differentiates the potential of Horus the Elder from the actualization of Horus the Younger. Here, it is Thoth who kicks off the introduction of Strife into the cosmos to create the opportunity for the roots to separate and for the daimons to actualize; later, we shall see that it Thoth who again allows the actualized daimons to reascend. In Egyptian myth, Thoth is said to be the husband of Maat, who I think is Empedoclean Necessity or Fate (Plutarch on the Generation of the Soul in the Timaeus XXVII; Hippolytus, Refutation of All Heresies VII xvii; Porphyry, quoted by Stobaeus, Eclogues II viii), which brings us full circle: it is the strict rule of Necessity that forces the daimons into exile for breaking their oaths and brings them back again when their debt has been paid in full, which is only accomplished when their Strife-riven roots are brought back into unity by means of Love. This is equivalent to the Egyptian image of Thoth weighing the dead person's heart against Maat's ostrich feather on a scale, and, if the two are exactly in balance, allowing the person to proceed on their journey home.

Phew! What an exhausting six weeks it has been since starting the myth back over, but it's been profitable. I think it's amazing how much depth these myths possess, but I hear my shoulder-Plotinus saying that the depth was already within me the whole time.

Here on this blog, I spend so much time on the philosophers and their metaphysics that it may surprise you to hear that my own personal theology is mostly drawn from Hesiod's Ages of Man. I didn't expect, in studying the Egyptian myth, to learn anything which would expand on that, and yet we've seen a couple parallels already: the theogony and the exile of daimons. Surely you all know by now how fond I am of the golden race, yes? So it must be no surprise to hear that my ears perked up when I heard Hippolytus saying, "Empedocles [...] wrote a great deal about the nature of daimons too, how they dwell in and administer affairs all over the earth, being very numerous." I had noted before that I despaired of being able to trace Hesiod's daimons back any further than Greece, and yet, with so many other precedents in Egyptian myth, perhaps the daimons, too, have theirs?

Now, I am not very far into reading Egyptian literature, but there seem to be a lot of Horuses: Horus himself, Horus of the Two Lands, Horus of Behdeti, Horus of the Horizon, and so on. Is it possible that "Horus," used in this way, simply refers to a daimon? That is, is Horus of the Two Lands the tutelary daimon of the unified state of Egypt? Is Horus of Behdeti is the tutelary daimon of the city of Behdeti? Is pharaoh identified with Horus because, like a tutelary daimon, it is his responsibility to guide and protect Egypt? It seems like it might be a profitable avenue of research to explore Egyptian myth with an eye towards such an interpretation...