Good morning, everyone, and a Happy Thanksgiving to those of you celebrating it tomorrow. Let's pick the puzzle-box back up, shall we?

IV. That the species of myth are five, with examples of each.

Of myths some are theological, some physical, some psychic,* and again some material, and some mixed from these last two. The theological are those myths which use no bodily form but contemplate the very essences of the Gods: e. g. Kronos† swallowing his children. Since God is intellectual, and all intellect returns into itself, this myth expresses in allegory the essence of God.

Myths may be regarded physically when they express the activities of the Gods in the world: e. g. people before now have regarded Kronos as Time, and calling the divisions of Time his sons say that the sons are swallowed by the father.

The psychic way is to regard the activities of the Soul itself: the Soul's acts of thought, though they pass on to other objects, nevertheless remain inside their begetters.

The material and last is that which the Egyptians have mostly used, owing to their ignorance, believing material objects actually to be Gods, and so calling them: e. g. they call the Earth Isis, moisture Osiris, heat Typhon, or again, water Kronos, the fruits of the earth Adonis, and wine Dionysus.‡

To say that these objects are sacred to the Gods, like various herbs and stones and animals, is possible to sensible men, but to say that they are gods is the notion of madmen—except, perhaps, in the sense in which both the orb of the sun and the ray which comes from the orb are colloquially called 'the Sun.'§

The mixed kind of myth may be seen in many instances: for example they say that in a banquet of the Gods Discord threw down a golden apple; the goddesses contended for it, and were sent by Zeus to Paris to be judged; Paris saw Aphrodite to be beautiful and gave her the apple. Here the banquet signifies the hyper-cosmic powers of the Gods; that is why they are all together. The golden apple is the world, which, being formed out of opposites, is naturally said to be "thrown by Discord." The different Gods bestow different gifts upon the world and are thus said to "contend for the apple." And the soul which lives according to sense—for that is what Paris is—not seeing the other powers in the world but only beauty, declares that the apple belongs to Aphrodite.

To take another myth, they say that the Mother of the Gods‖ seeing Attis lying by the river Gallus fell in love with him, took him, crowned him with her cap of stars, and thereafter kept him with her. He fell in love with a nymph and left the Mother to live with her. For this the Mother of the Gods made Attis go mad and cut off his genital organs and leave them with the Nymph, and then return and dwell with her.

Now the Mother of the Gods¶ is the principle that generates life; that is why she is called Mother. Attis is the creator# of all things which are born and die; that is why he is said to have been found by the river Gallus. For Gallus signifies the Galaxy, or Milky Way, the point at which body subject to passion begins.Δ Now as the primary gods make perfect the secondary, the Mother loves Attis and gives him celestial powers. That is what the cap means. Attis loves a nymph: the nymphs preside over generation, since all that is generated is fluid. But since the process of generation must be stopped somewhere, and not allowed to generate something worse than the worst, the Creator who makes these things casts away his generative powers into the creation and is joined to the gods again.◊ Now these things never happened, but always are. And Mind sees all things at once, but Reason (or Speech) expresses some first and others after.↓ Thus, as the myth is in accord with the Cosmos, we for that reason keep a festival imitating the Cosmos, for how could we attain higher order?

And at first we ourselves, having fallen from heaven and living with the Nymph, are in despondency, and abstain from corn and all rich☞ and unclean food, for both are hostile to the soul. Then comes the cutting of the tree and the fast, as though we also were cutting off the further process of generation. After that the feeding on milk, as though we were being born again; after which come rejoicings and garlands and, as it were, a return up to the Gods.

The season of the ritual is evidence to the truth of these explanations. The rites are performed about the Vernal Equinox, when the fruits of the earth are ceasing to be produced, and day is becoming longer than night, which applies well to Spirits rising higher. (At least, the other equinox is in mythology the time of the Rape of Korê,❦ which is the descent of the souls.)

May these explanations of the myths find favour in the eyes of the Gods themselves and the souls of those who wrote the myths.

* Thomas Taylor translates these five kinds of fables similarly, but instead of "psychic," he calls that kind "animastic (or belonging to soul)."

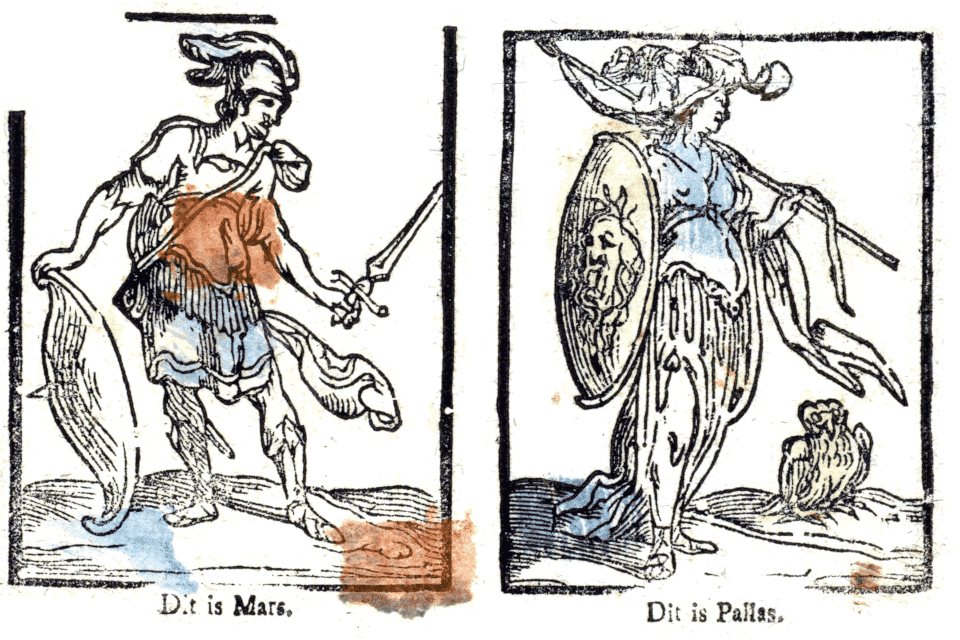

† This is probably of interest to none save myself, but here and below, Taylor favors the Roman deities rather than the Greek: Saturn, Bacchus, Jupiter, Venus, Proserpine. Curiously, Gilbert Murray and Arthur Darby Nock retain the Greek deities from the original but nonetheless name Discord and Strife, respectively (rather than Eris).

‡ Nock notes, "As Wendland remarks, Berl. phil. Woch. 1899, 1411, this sentence, in which Greek gods are named after Egyptian deities, apparently as in the same category, is clumsy, but the clumsiness may well be due to the author."

§ Murray notes, "e.g. when we say 'The sun is coming through the window,' or in Greek ἐξαίφνης ἥκων ἐκ τοῦ ἡλίου ['exaiphnes hekon ek tou heliou'], Plat. Rep. 516 E. This appears to mean that you can loosely apply the term 'Osiris' both to (i) the real Osiris and (ii) the corn which comes from him, as you can apply the name 'Sun' both to (i) the real orb and (ii) the ray that comes from the orb. However, Julian, Or. v, on the Sun suggests a different view—that both the orb and the ray are mere effects and symbols of the true spiritual Sun, as corn is of Osiris.

‖ Taylor notes, "See more concerning this species of fables in my Dissertation on the Eleusinian and Bacchic Mysteries."

¶ Kybele.

# Here and below, Taylor translates "Creator" as "Demiurgus." Curiously, Murray capitalizes "Creator" below, but leaves it lowercase here.

Δ Murray notes, "ἄρχεσθαι ['archesthai'] Mr. L. W. Hunter, ἔρχεσθαι ['erchesthai'] MS. Above the Milky Way there is no such body, only σῶμα ἀπαθές ['soma apathes']. Cf. Macrob. in Somn. Scip. i. 12."

◊ Taylor notes, "This explanation of the fable is agreeable to that given by the Emperor Julian, in his Oration to the mother of the gods, my translation of which let the reader consult."

↓ Nock notes, "As Praechter explains, W. kl. Ph. 1900, 184, what is ever present to the nous is projected into the succession of historical events."

☞ Nock notes, "As for instance pomegranates, dates, fish, pork (H. Hepding, Attis, 156 f.)."

❦ Persephone.