Before digging into a work, I like to know a little about where the author is coming from. My book on Plotinus has an adequate little biography of him (an abridgment of Porphyry's), but of MacKenna, the translator, nothing is; what one finds of him, looking online, is a mystery. Not in that he is obscure, but in that he is a thread that, being tugged, draws you down the rabbit-hole into a still-greater mystery, one which enchants and bewitches and entices and maddens. That is all to say, MacKenna seems to have been very interesting indeed.

So to attempt to get a sense of the man, I turn to his published letters and diary, and clicking around randomly—ha!—brought me to a letter from MacKenna to Sir Ernest Debenham, penned in January of 1916 (and hastily transcribed by me, so I apologize for any errors):

I hope you and yours are well and as happy as the dismal times allow: myself I sicken at the all the blood, the mowing down of the youth of Europe, the stop, dead, of all we have thought of civilization, the multiform, wide as the world almost, agony and desolation. Plotinus mocks at all such emotions—if I weren't too lazy I'd transcribe a passage ad hoc, very fine as literature but dreadfully unreal to-day, at least to my lower sense—and this tho' Plotinus had been a soldier and seen, ce qu'on appelle vu ["what we call seen"], on no small scale too, the horrors of which his "Sage"—really our "Saint" tho' one daren't use the word— declares a trivial ragged fringe on his beautiful inner peace. For my part I find this war, with all that it entails to the world and to my own poor little land, setting me blaspheming. I see men as trees walking—soulless motion merely, and no purpose over it all—perhaps beasts ravening would be better, nearer to my mind, and no thought ruling the rage even to some sound material end. I suppose in the light of history all this is absurd—and then Plotinus would be right—all comes out smiling at the end, and the fall of one civilization is the beginning of another: if the Yellow Peril that once was a music-hall joke turned into a Yellow Actuality and all the world was yellow, there would once be once more arts and religions and contempt for the ancient and passed thing with lyric celebrations of the triumph of light at last. The world certainly renews itself, and always manages, with relatively brief periods of disaster and ugliness, to keep a sober average—but at the moments of ugliness, it is no pretty thing, no cheerful sight, and we get a sharp reminder (which our history is generally too dead in our minds to give us) that all our "truths" are merely dreams and that nothing is sure but birth and death, both sure but dark in their meaning. The God of the world is discovered to be an incalculable: we do not know what he is up to, or whether there is any care up there at all: ["but he is impious"], says Æschylus of the man that thinks this, that Gods do not deign to care for the good and ill doings of men: I'm afraid I'm ["impious"]. Of course, by the way, so is Plotinus in this: his Supreme is

too great and different to care: it is man that must care; and on that Plotinus gets as stern a moral code as others get out of the God who is offended and appeased and always working at the wheel of the world. The Father's house has many mansions and still more approaches: all roads lead to its peace, and a good Plotinian would be undistinguished in life from a good Christian, except perhaps being better.

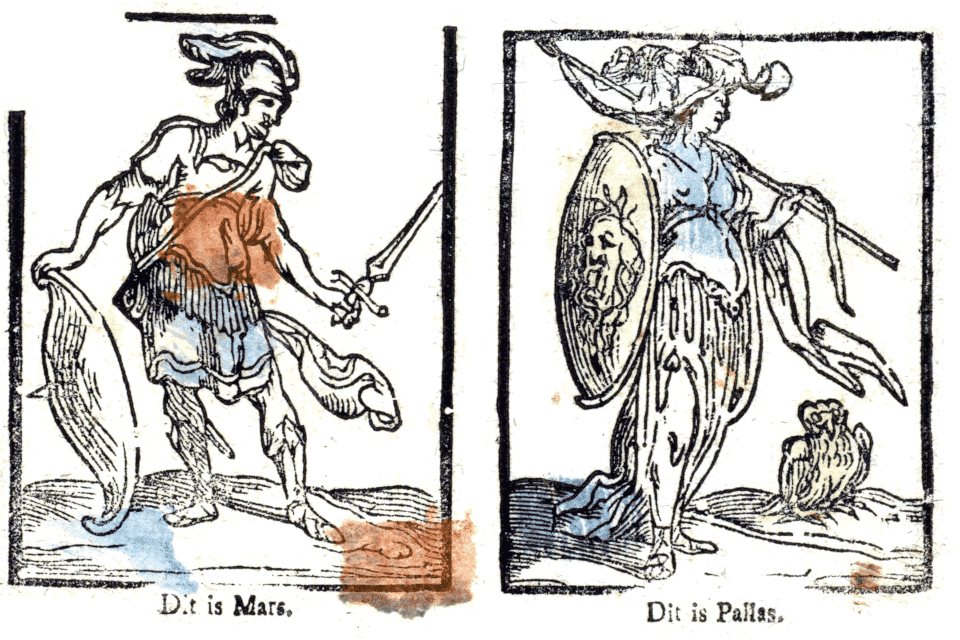

I imagine we will, ourselves, be in the same times MacKenna lamented quite soon! But the dance of Mars gives way to the dance of Venus, just as the dance of Venus gives way to the dance of Mars. If we embrace the show of Venus in all Her beauty and grace and joy and voluptuousness, should we not, too, embrace the show of Mars? Sure, it may be dirty and hard and sorrowful and severe, but ah! what He brings with Him!

I am reminded of a Sufi parable:

A dervish fell into the Tigris. Seeing that he could not swim, a man on the bank cried out, "Shall I tell some one to bring you ashore?" "No," said the dervish. "Then do you wish to be drowned?" "No." "What, then, do you wish?" The dervish replied, "God's will be done! What have I to do with wishing?"

Perhaps we each have our favorite Divinity, but nonetheless may we all learn and learn well to trust all Divinity, and in so doing learn to appreciate every dance.