Mnesarchos the Samian was in Delphi on a business trip, with his wife, who was already pregnant but did not know it. He consulted the Pythia about his voyage to Syria. The oracle replied that his voyage would be most satisfying and profitable, and that his wife was already pregnant and would give birth to a child surpassing all others in beauty and wisdom, who would be of the greatest benefit to the human race in all aspects of life. Mnesarchos reckoned that the god would not have told him, unasked, about a child, unless there was indeed to be some exceptional and god-given superiority in him. So he promptly changed his wife's name from Parthenis to Pythais, because of the birth and the prophetess. When she gave birth, at Sidon in Phœnicia, he called his son Pythagoras ["Pythia speaks"], because the child had been foretold by the Pythia.

(Iamblichus, On the Pythagorean Life, as translated by Gillian Clark)

Well, Chærephon, as you know, was very impetuous in all his doings, and he went to Delphi and boldly asked the oracle to tell him whether [...] there was anyone wiser than I was, and the Pythian prophetess answered that there was no man wiser. [...]

When I heard the answer, I said to myself, "What can the god mean? and what is the interpretation of this riddle? for I know that I have no wisdom, small or great. What can he mean when he says that I am the wisest of men? And yet he is a god and cannot lie; that would be against his nature." [...]

The truth is [...] that God only is wise; and in this oracle he means to say that the wisdom of men is little or nothing; he is not speaking of Socrates, he is only using my name as an illustration, as if he said, "He [...] is the wisest, who, like Socrates, knows that his wisdom is in truth worth nothing."

(Socrates, as quoted by Plato, and as translated by Benjamin Jowett)

Apollo was consulted by Amelius, who desired to learn where Plotinus' soul had gone. [...]

Celestial! Man at first but now nearing the diviner ranks! the bonds of human necessity are loosed for you and, strong of heart, you beat your eager way from out the roaring tumult of the fleshly life to the shores of that wave-washed coast free from the thronging of the guilty, thence to take the grateful path of the sinless soul: where glows the splendour of God, where Right is throned in the stainless place, far from the wrong that mocks at law.

Oft-times as you strove to rise above the bitter waves of this blood-drenched life, above the sickening whirl, toiling in the mid-most of the rushing flood and the unimaginable turmoil, oft-times, from the Ever-Blessed, there was shown to you the Term still close at hand:

Oft-times, when your mind thrust out awry and was like to be rapt down unsanctioned paths, the Immortals themselves prevented, guiding you on the straightgoing way to the celestial spheres, pouring down before you a dense shaft of light that your eyes might see from amid the mournful gloom.

Sleep never closed those eyes: high above the heavy murk of the mist you held them; tossed in the welter, you still had vision; still you saw sights many and fair not granted to all that labour in wisdom's quest.

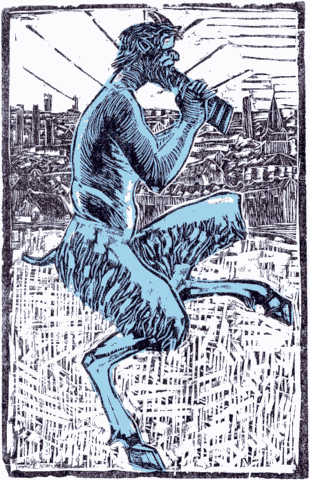

But now that you have cast the screen aside, quitted the tomb that held your lofty soul, you enter at once the heavenly consort: where fragrant breezes play, where all is unison and winning tenderness and guileless joy, and the place is lavish of the nectar-streams the unfailing Gods bestow, with the blandishments of the Loves, and delicious airs, and tranquil sky: where Minos and Rhadamanthus dwell, great brethren of the golden race of mighty Zeus; where dwell the just Æacus, and Plato, consecrated power, and stately Pythagoras and all else that form the Choir of Immortal Love, that share their parentage with the most blessed spirits, there where the heart is ever lifted in joyous festival.

O Blessed One, you have fought your many fights; now, crowned with unfading life, your days are with the Ever-Holy.

(Porphyry, Life of Plotinus, as translated by Stephen MacKenna)

[Julian] sent Oribasius, physician and quæstor, to rebuild the temple of Apollo at Delphi. Arriving there and taking the task in hand, he received an oracle from the dæmon:

Tell the emperor that the Daidalic hall has fallen.

No longer does Phœbus have his chamber, nor mantic laurel,

Nor prophetic spring, and the speaking water has been silenced.

(George Kedrenos, as translated by Timothy E. Gregory)