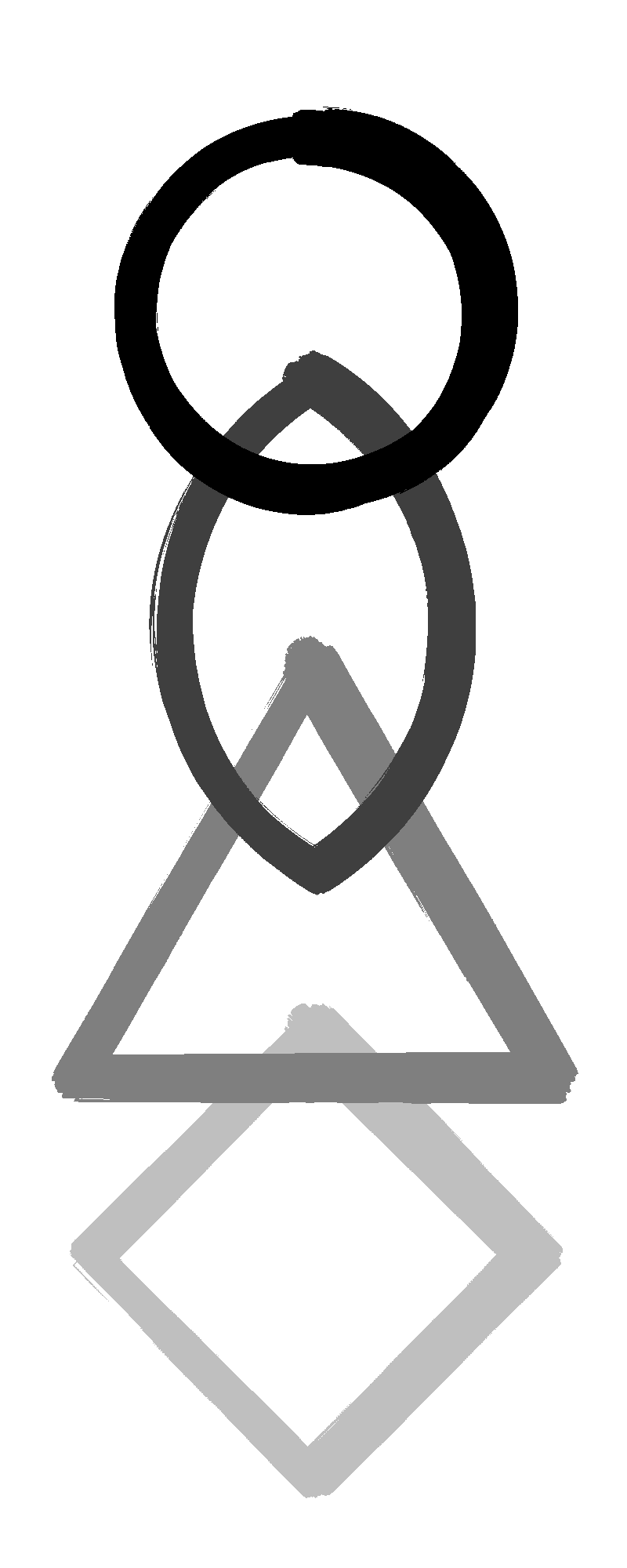

Tao gives birth to One.

One gives birth to Two.

Two gives birth to Three.

Three gives birth to everything.

But everything carries yin and embraces yang.

And yin and yang, together, are One.

(Tao Te Ching, 42)

I am One transformed into Two;

I am Two transformed into Four;

I am Four transformed into Eight;

I am, after this, One.

(The Coffin of Petamun)

As all things were produced by the mediation of the one,

so all things were produced from the one by adaption.

(The Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus)

I was trying to explain Neoplatonist metaphysics to a computer programmer friend the other day and stumbled onto a useful analogy which might help to explain the idea of hypostases.

Are you familiar with the fundamental theorem of arithmetic? It states that every integer greater than one can be uniquely represented as a product of prime numbers, that is, that every number is equivalent to 2a·3b·5c·7d·11e·13f⋯. Wikipedia gives the useful example that the number 1200=24·31·52.

So, suppose you have a box somewhere which can contain exactly one number. It doesn't matter how large this number is, just that it can only contain one of them. If you want to store a single number, great, you can just stuff it into the box and you're done.

But what if you want to store two numbers? Well, thanks to the fundamental theorem of arithmetic, we can cheat: suppose we call the first a and the second b, then we can find 2a·3b. This is fine since the result will be a unique number, we can stuff it into the box, and we'll always be able to pull a and b back out of it again if we need to.

If we want to store three or ten or a hundred numbers, it's the same thing again: we need more prime numbers, but we'll still get one resulting number in the end. The more numbers we want to store, the more ridiculously huge that result will be, but the box doesn't care how big it is, and so it's no problem. In fact, we can do this no matter how many numbers we have.

So in this way, a single box is, in fact, equivalent to a row of pseudo-boxes. But wait, there's no reason we have to stop there: each pseudo-box in the row is equivalent to a row of its own, right? So by repeating the process on each pseudo-box in the row, that single real box is equivalent to a two-dimensional grid represented by rows and columns of pseudo-pseudo-boxes. And we can repeat the process again on each pseudo-pseudo-box, making something of a cube of pseudo-pseudo-pseudo-boxes. And we can repeat the process again, and so on. We started with a zero-dimensional grid of boxes (that is, a point), but through a transformation process, found we could produce a one-dimensional grid of boxes (that is, a line), or a two-dimensional grid of boxes (that is, an area), or a three-dimensional grid of boxes (that is, a volume), or as many dimensions as you like. And these productions are inherent simply from the original box existing—it doesn't involve doing anything, it's just a matter of how we interpret it.

The connection to Neoplatonism is that the only thing that exists is the One, which is our single box, the only one that really exists; but this box is virtually a line of boxes, which is like all of the distinct ideas of the Intellect; but this line of boxes is virtually a grid of boxes, which is like all the distinct beings of the Soul; but this grid of boxes is virtually a volume of boxes, which is like all the various lives of those souls; but this volume of boxes is...